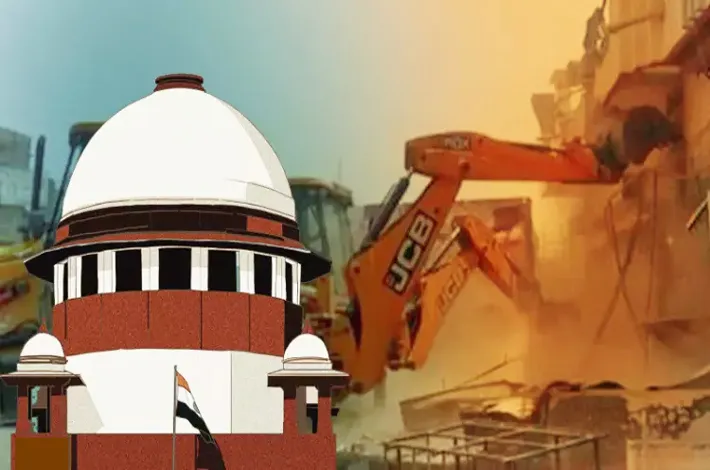

Bulldozer shows power, not justice

06-02-2026 12:00:00 AM

Bulldozer justice has no rationale whatsoever. It is nothing less than the state arrogating to itself the roles of judge, jury, and executioner. In a constitutional democracy governed by the rule of law, such conduct is not merely excessive; it is unlawful. Yet, governments like that of Uttar Pradesh behave as though demolishing homes is their inalienable right, a swift and spectacular way to punish those they presume to be guilty.

The Constitution does not permit this. No civilised society can justify it. Punishment is not the prerogative of the executive; it belongs exclusively to the judiciary after due process of law. The spectacle of bulldozers tearing down homes within hours or days of an offence being registered is a chilling reminder of how fragile constitutional guarantees can become when brute majoritarian power replaces legal restraint.

The Supreme Court put this beyond doubt in November 2024 when it held that demolishing properties of accused persons as a punitive measure is illegal. The court laid down clear guidelines: illegal constructions can be removed only after following due process, issuing adequate notice, giving the occupants an opportunity to respond, and ensuring that the action is not arbitrary or vindictive. Demolition, the court said, cannot be used as punishment. Yet, as the Allahabad High Court observed on Tuesday, the practice continues unabated in Uttar Pradesh.

A bench of Justices Atul Sridharan and Siddharth Nandan openly questioned whether the Supreme Court’s directions are being followed at all. More importantly, it asked a fundamental question: is the state’s duty to demolish homes or to protect the rights of its citizens? There is no provision in Indian law that allows property to be destroyed as a form of punishment. Still, bulldozer action has become disturbingly commonplace in BJP-ruled states, often carried out soon after the registration of an offence.

The High Court rightly noted that such demolitions may amount to a “distorted exercise of executive discretion”. In plain terms, they reek of vengeance, not justice. What makes this practice especially indefensible is that homes are demolished simply because an accused person resides there. It does not matter that the same house shelters elderly parents, a wife, or young children. They are punished without charge, trial or conviction. Collective punishment of this kind is alien to Indian constitutional values and echoes the methods of authoritarian regimes, not a republic founded on liberty and equality.

The High Court’s reminder that even a “reasonable apprehension” of demolition entitles citizens to approach the courts is telling. When fear itself becomes grounds for legal protection, it signals a profound erosion of trust in the executive. Bulldozers may project power, but they also expose the state’s contempt for due process. A government that demolishes first and asks questions later is not enforcing the law; it is dismantling it.