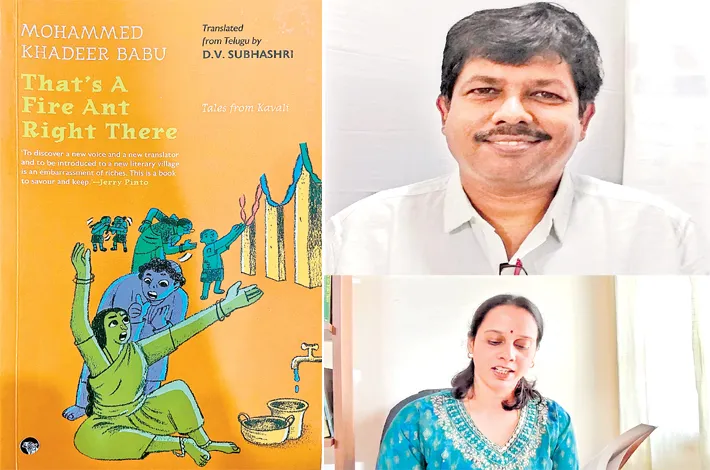

A sparkling translation

25-10-2025 12:00:00 AM

An expanded review of “That's A Fire Ant Right There”: Tales from Kavali

Each story is a gem, concise but layered, evoking the brevity of Chekhov but steeped in coastal Andhra's salty air

In the colourful fabric of Indian literature, regional voices often struggle to break through linguistic barriers, translations serve as vital bridges. Mohammed Khadeer Babu's That's A Fire Ant Right There: Tales from Kavali, deftly translated into English by DV Subhashri and published by Speaking Tiger Books, is a triumphant example. This 288-page collection of 50 short stories, priced at Rs 499, draws readers into the sun-baked streets and intimate family hearths of Kavali, a coastal town in Andhra Pradesh's Nellore district. At just over a month old, the book has already garnered praise for its unpretentious charm, earning a perfect 5.0 rating on Amazon from early readers who celebrate its "witty storytelling in the Nellore dialect." For English-speaking audiences, it's not just a window into Telugu literature—it's a revelation of how everyday magic thrives in the margins.

Khadeer Babu embodies the multifaceted spirit of contemporary Telugu writing. A journalist, editor, and Telugu film scriptwriter, he has long been a beloved figure in his hometown, where his stories resonate like local folklore. His earlier collections, such as Dargamitta Kathalu, have sold widely, capturing the pulse of small-town life with humor and humility. Unlike grand epics or polemical novels, Khadeer's tales are slices of childhood unadorned—no heroic swells, just the quiet heroism of survival and joy. He unwittingly pioneers a fresh vein in Telugu childhood literature, building on trailblazers like Namini while infusing it with the rhythmic cadence of Nellore's Muslim families. His narratives avoid glorification, opting instead for raw truth, much like Suseela Somaraju's Illeramma Kathalu. These stories "draw from his childhood memories," transforming personal anecdotes into universal touchstones.

Subhashri, the Bangalore-based multilingual writer who makes this alchemy possible. A prolific translator working across Telugu, Kannada, and Hindi into English, Subhashri's portfolio includes stories in outlets like Out of Print Magazine and her own published fiction. This is her second collaboration with Khadeer, following another acclaimed translation that preserved the "richness of the original." Translation, as everyone from the 1985-86 Osmania University symposium on Contemporary Indian Literature would attest, is literature's toughest craft—harder than original creation. There, Telugu representatives like Prof. Kothapalli Veerbhadra Rao faced stark truths: despite schemes like the Sahitya Akademi's, too few Telugu works cross into other languages. Subhashri confronts this head-on, especially with Khadeer's hyperlocal dialect, which she describes in her translator's note as "impossible to replicate in plain English" due to its humorous curves. She retains Telugu words, phrases, and names—dadima for grandmother, nannamma for maternal kin—allowing the stories' fragrance to seep through without jarring the English flow.

The result? A collection that pulses with life. Populated by strong women hawking flowers at dawn, cheeky scamps dodging schoolyard tyrants, virtuous dawdlers philosophizing over chai, and scrupulous teachers wielding chalk like scepters, these tales offer a riveting portrayal of community bonds. Each story is a gem, concise but layered, evoking the brevity of Chekhov but steeped in coastal Andhra's salty air. Take "Me on the Floor, My Mother on the Bench," a poignant vignette of filial tenderness amid poverty. The young narrator sprawls on the cool earth while his mother perches above, her weary hands mending dreams as much as clothes. It's a scene that lingers, highlighting Khadeer's gift for turning scarcity into subtle abundance. Similarly, "My Mother's Flower Business" bursts with sensory delight: the predawn bustle of Nellore's markets, petals crushed underfoot, bargains struck in a dialect that dances like monsoon winds. Here, the mother's resilience shines, her entrepreneurial spirit a quiet feminist anthem in a patriarchal backdrop.

Humor, that elusive sprite, is Khadeer's secret weapon, and Subhashri captures it deftly. "Roti Festival at Dargamitta" transforms a neighborhood feast into farce, with overzealous cooks flipping flatbreads into aerial acrobatics and children staging mock battles with spilled dough. The chaos mirrors life's joyful disorder, laced with the dialect's puns that Subhashri footnotes just enough to illuminate without over-explaining. Then there's "Yama Kotings in MR Tutorials," a riotous skewering of exam-season superstitions—ghostly guardians (Yamabeing the god of death) invoked to ward off flunking fates. It's a nod to the universal student dread, but rooted in Kavali's tutorial sweatshops, where combined studies on terraces like in "Combined Study at Sridhar’s Terrace" devolve into gossip-fueled all-nighters.

Deeper themes emerge upon rereading. "My Dadima, His Nannamma and a Mamma in Between" weaves intergenerational threads, exploring how elders' lore—tales of Partition-era migrations and lost loves—shapes young hearts. Khadeer doesn't romanticize; he humanizes, showing fractures in family fabrics mended by shared laughter. "Exam Bells Are Ringing" extends this to societal pressures, where academic bells toll like funeral dirges for innocence lost. These stories are "captured in the innocent gaze of childhood," offering solace in a hurried world. They subtly critique without preaching, illuminating Muslim life in rural Andhra with authenticity that feels like eavesdropping on a family dinner.

What elevates this book beyond regional delight is its broader resonance. In an era of homogenized global narratives, Khadeer's work—now accessible via Subhashri's labor—revitalizes the short story form. It echoes the untranslatable woes voiced at that Osmania symposium, where scholars lamented the neglect of Telugu gems like Sripadam Subramanya Sastry's dialect-driven tales or Satyam Sankaramanchi's Amaravati Kathalu. Subhashri scores an 8/10 for fidelity; the dialect whispers rather than roars in English, but the spirit endures. One imagines Khadeer, with his journalist's eye, offering inputs during translation, fostering a synergy that feels collaborative.

‘That's A Fire Ant Right There’ isn't mere nostalgia; it's a beacon for Telugu literature's global aspirations. As Borderless Journal features excerpts that tease its depth, the book invites us to savour the "fire ant" sting of wit amid sweetness. Kudos to Khadeer for unearthing these memories and Subhashri for gilding them in English. Their partnership, like the stories themselves, humbles and heals. Aim for the International Booker Prize? Absolutely—they've earned the shot. For lovers of slice-of-life prose, from Ruskin Bond's hills to Jhumpa Lahiri's diasporas, this is essential reading. Dive in; you'll emerge smelling of jasmine and sea salt, and the smell of Earth of Nellore.