Why People oppose Bill Gates visit to ap?

16-02-2026 12:00:00 AM

What Bill said…

"India is an example of a country where there's plenty of things that are difficult there - the health, nutrition, education is improving and they are stable enough and generating their own government revenue enough that it's very likely that 20 years from now people will be dramatically better off and it's kind of a laboratory to try things that then when you prove them out in India, you can take to other places." He added that the Gates Foundation has its largest non-US office in India and runs the most pilot projects there with local partners.

Why the mistrust

- HPV vaccine trials (2009–10) in Andhra Pradesh, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and run by PATH, were later criticized by a parliamentary panel for ethical lapses, creating long-term distrust.

- Past remarks by Bill Gates describing India as a testing ground reinforced fears of vulnerable communities being used for experimentation.

- Promotion of corporate-backed seeds and agri-tech revives anxieties linked to the Bt cotton era and farmer indebtedness.

- AI-driven health records and farm databases raise concerns about data privacy, surveillance, and foreign access to sensitive information.

- Post-COVID misinformation and vaccine skepticism have fueled conspiracy theories about Gates’ influence on public health.

- Critics argue such partnerships risk undermining India’s policy sovereignty and increasing corporate influence.

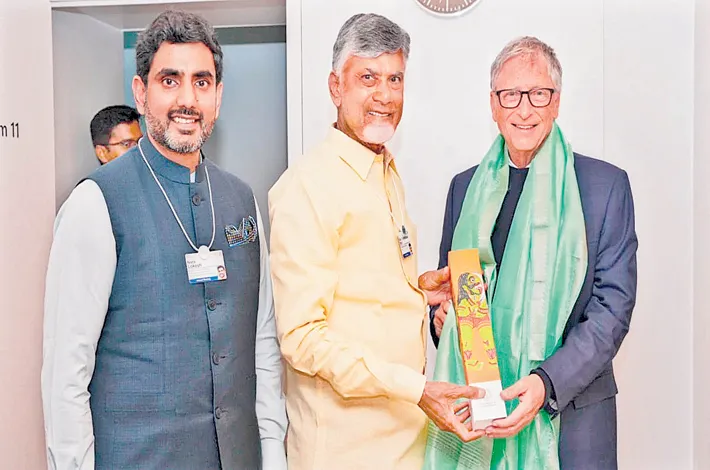

There is a simmering opposition to Bill Gates visit to Andhra Pradesh on Monday. The Microsoft co-founder and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation chair will meet Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N. Chandrababu Naidu, Deputy CM Pawan Kalyan, and IT Minister Nara Lokesh to review collaborations in healthcare, agriculture, and education. A 2025 MoU promises AI-powered tools: digital health records under the Sanjeevani project, personalized medicine, precision farming via satellite imagery, and tech upgrades for schools. Naidu calls it a game-changer for his “Swarna Andhra 2047” vision—a $2.4 trillion economy driven by data and innovation.

But yet, the visit has ignited fierce opposition, loudest in Andhra Pradesh but echoing across India. Social media erupts with #ArrestBillGates and calls to bar him from the country. Activists, farmers, and opposition voices see not benevolence, but a pattern of corporate influence, ethical shortcuts, and threats to sovereignty. This is no fringe conspiracy; it taps into real historical grievances, amplified by post-colonial sensitivities and rural anxieties.

A national backlash rooted in history

India’s unease with Gates is not new. In 2009-2010, the Gates Foundation funded PATH to run HPV vaccine “demonstration projects” in Khammam district of (then-undivided) Andhra Pradesh and Vadodara in Gujarat. Over 23,000 girls, mostly from poor tribal and rural families aged 9-15, received doses of Merck’s Gardasil and GSK’s Cervarix. Seven died—five in AP. Official probes by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) found no direct vaccine link, attributing deaths to causes like malaria, suicide, and accidents. But a 2013 parliamentary standing committee report was damning: consent was often obtained via school principals rather than parents, many illiterate; counseling was inadequate; and participants lacked insurance. The committee accused PATH and partners of “gross violations” of ethics, treating India as a testing ground for eventual inclusion in the universal immunization program.

The scandal led to temporary restrictions on the Foundation’s role in national immunization. Though the Foundation defended the trials as ethical and life-saving—HPV causes cervical cancer, a major killer of Indian women—the episode cemented a narrative: Western philanthropists experiment on the vulnerable. Gates’ own 2010s comments framing India as a “laboratory” for scalable solutions only poured fuel on the fire.

Agriculture deepens the rift. The Foundation champions climate-smart seeds, digital advisories, and public-private partnerships. Critics link this to the controversial Bt cotton rollout in the 2000s, where farmer suicides spiked amid debt from expensive seeds and pesticides (though causation remains debated). Recent Microsoft-Government MoUs for farmer databases—accessing land records for millions—raise alarms of data privatization. In a country where 60% of the population depends on farming, handing personal and agricultural data to Big Tech feels like handing over the keys to corporations.

Post-COVID vaccine skepticism has supercharged these fears. While the Foundation supported India’s Covaxin and Covishield rollout, online narratives tie Gates to “depopulation agendas,” microchipping, and undue influence. His documented meetings with Jeffrey Epstein, revealed in court files, add a layer of personal revulsion for many. In a deeply religious and nationalist India, a billionaire outsider shaping health and food policy triggers visceral resistance.

Andhra Pradesh: Where History Hits Home

Opposition burns hottest in Andhra. Khammam’s HPV trials happened here, in tribal hamlets where families still recall the deaths and the subsequent outcry. The current MoU revives those ghosts. The Sanjeevani project’s digital health push—centralized records, AI diagnostics—promises efficiency but raises privacy nightmares in a state with patchy data protection and histories of Aadhaar-linked exclusions.

Farmers’ groups, scarred by decades of agrarian distress, view AI-driven agriculture as the next corporate Trojan horse. Andhra has experimented with zero-budget natural farming under the previous YSRCP regime; tech-heavy models from Seattle feel like a reversal favoring multinationals. Opposition parties like YSRCP have seized the moment, accusing Naidu’s TDP-led government of “selling out” to foreign interests amid local issues like temple controversies and power tariffs.

Social media in Telugu and English bristles with memes: “Bill gAIDS,” Epstein jabs, and warnings of “mass murderer” welcomed by the state. An open letter circulating online urges Gates to reconsider investments, citing governance concerns under Naidu. While mainstream protests remain small, the sentiment is widespread—rural WhatsApp forwards, village tea stalls, and urban activist circles all echo the same distrust.

Why the Resistance Persists

This opposition is not mere paranoia. It reflects genuine power imbalances. In a rising, sovereign India, Western philanthropists—however well-intentioned—carry the baggage of colonial-era “civilizing missions.” Rural India, where small farmers battle climate shocks and market volatility, sees tech solutions as top-down impositions rather than empowerment. Data is the new oil; handing health and farm records to entities tied to global capital feels like surrendering control.

In Andhra Pradesh, the backlash is particularly pointed because the stakes are local. The state’s farmers and tribal communities have paid the price of past “experiments.” Naidu’s aggressive modernization drive, while visionary to supporters, feels tone-deaf to those who remember Khammam.

As Gates touches down, expect symbolic protests—effigies, black flags, online storms. The government will highlight jobs, health gains, and innovation. The real story, though, is the widening chasm between elite optimism about global partnerships and grassroots fears of exploitation. Bridging it will require more than MoUs: radical transparency, community consent, and proof that technology serves the tiller, not just the algorithm.

For now, the opposition speaks volumes about a nation no longer willing to be anyone’s laboratory.