Busting Myths Surrounding Urdu

30-08-2025 12:00:00 AM

Venkat Parsa

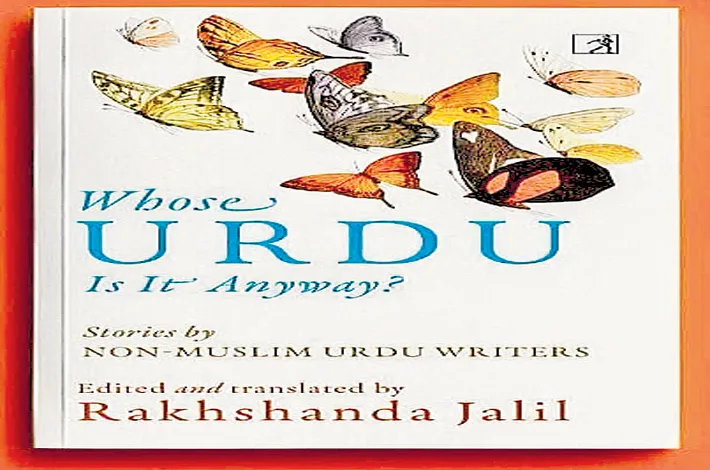

Urdu is either eulogized as the language of poetry, or simply dismissed as the language that merely deals with Muslim subjects. Rakhshanda Jalil, renowned author, critic, translator and literary historian, through her latest book, Whose Urdu Is It Anyway? Stories by Non-Muslim Urdu Writers, helps bust the myth that Urdu is the language of the Muslims.

This book is a collection of 16 Stories, of the likes of Krishan Chander, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Ramanand Sagar and Kanhaiya Lal Kapoor, among others. It has been translated from Urdu into English and edited by Rakhshanda Jalil. This book, says Rakhshanda, is an attempt to bust stereotypes and address a persistent misconception: that Urdu is the language of India’s Muslims and that it addresses subjects that are, or should be, of concern to Muslims and Muslims alone. Aim, she says, is to locate Urdu in its rightful place — in the heart of Hindustan.

Mistaken Impression

Rakhshanda Jalil notes that Muslims in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Assam, Bengal, and Kashmir don’t speak Urdu. Yet, in regions like Hyderabad State, Bhopal, Lucknow, and Punjab, Urdu was spoken by both Hindus and Muslims. Urdu symbolizes Hindu-Muslim unity, born in military camps through linguistic intermingling. Rooted in Indian soil, it shares grammar with Hindi, blending Khari Boli with Persian, Arabic, and Turkish—making it as Indian as Sanskrit.

Language of freedom struggle

Rakhshanda Jalil is instrumental in pointing out how Urdu is the language of the Freedom Struggle, of Bhagat Singh Singh and Ramprasad Bismil and of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. Maulana Hazrat Mohani (on whom Rakhshanda is writing a book) gave the inspiring slogan that set the freedom struggle on fire: Inquilaab Zindabad or Long Live the Revolution.

Bhagat Singh wrote a piece at the age of 15 years, dedicating his life to the nation in Urdu and his last letter to his brother was in Urdu. Ramprasad Bismil penned the stirring composition, Sarfaroshi ki tamanna ab humare dil mein hai. Netaji named his Army as Azad Hind Fouj and gave the stirring call, Tum mujhe khoon do, main tumhe Azaadi doonga (Give me blood, I will give you freedom). Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru gave a speech in Urdu, while moving the Aims and Objectives Resolution in the Constituent Assembly on December 13, 1946.

Irony of History

Ironically, Urdu—a language of the Freedom Struggle—declined post-Independence, largely due to Pakistan adopting it as its national language. In the Constituent Assembly, the vote on India’s official language ended in a 78-78 tie. Dr. Rajendra Prasad’s casting vote went to Hindi, against Gandhi and Nehru’s preference for Hindustani. Later, campaigns led by editors like Dharamvir Bharti pushed for Sanskritized Hindi, stripping the language of its original flavour.

400-Year Literary History

Urdu has a literary history and tradition of at least 400 years, from the time of the first Diwan in Urdu poetry, Quliyaat-e-Mohammad Quli Qutub Shah. Popular Hindi Literature is about 140 years old, or at the most 175 years old. Hindi is more a Link Language between Khari Boli, Awadhi and Braj Bhasha.

On the other hand, Urdu has greater claim to be the Link Language of India. Unlike Hindi, limited only to the Hindi-heartland, Urdu has geographic spread, from Punjab, Lucknow and Bhopal to former Hyderabad State in the South. On the other hand, Pakistan has no place where Urdu is spoken. It has Pakhtun, Punjabi and Sindhi. Bangladesh broke away, reasserting the Bengali Pride. Where is Urdu in Pakistan?

Cradle of Urdu

While Urdu is often fancifully claimed to have had its birth in Meerut in Uttar Pradesh, erstwhile Hyderabad State, not Telangana, is the Cradle of Urdu. It spread from Aurangabad in Maharashtra, through Hyderabad, right up to Gulbarga in Karnataka.

First Diwan of Urdu poetry that predates Diwan-e-Ghalib of Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib is Quliyaat-e-Mohammad Quli Qutub Shah, who founded Hyderabad in 1591. Wali Deccani was based in Aurangabad, former Capital of Hyderabad State. Last of the great Urdu poets, Maqdoom Mohiuddin, Lecturer in City College, was also from Hyderabad.

Film Based on Hyderabad

An old Hindi film, made in 1960, Madhubala-Bharat Bhushan-Shyamaastarrer, Barsaat Ki Raat, captures it all on the silver screen. Madhubala, playing the role of Shabnam, is the daughter of Hyderabad Police Commissioner, who falls in love with qawwal Aman, played by Bharat Bhushan. They elope to Lucknow and then to Ajmer, where there's the finale of the Qawwali contest, ending in uniting the lovers.

That Qawwali eulogizes love as divine. Penned by Sahir Ludhianvi, it compares love to Krishna, Radha and Meera; to Moses and Mount Sinai.

Jab jab Krishn ki Bansi baaji,Nikali Raadhaa saj keJaan ajaan ka dhyaan bhulaa ke,

Lok laaj ko taj ke (When Krishna played his flute, Radha would set out in search of Him; forgetting all that she has learnt).

Darshan jal ki pyaasi Meera Pi gayi vishh ka pyaalaa aur phir araj kari

Lok laaj raakho (With thirst for seeing her Lord, she quietly drank the cup of poison and prayed for protecting the honour of the society).

Ishq aazad hai, Hindu na Musalmaan hai ishq, Aap hi Dharam hai aur aap hii Imaan hai ishq Jis se aage nahi na Shekh-o-Brahaman donon Us haqeeqat ka garajtaa hua Elaan hai Ishq

(Love is free, love is neither Hindu nor Muslim; Love is Duty, Love is Faith; None is ahead of it, neither the Sheikh nor Brahmin; the thundering Proclamation of this highest reality is Love). Ishq Sarmad, Ishq hi Mansoor hai Ishq Moosa, Ishq Koh-e-Toor hai Khaaq ko Buth, aur Buth ko Devtaa karta hai Ishq (Love is everlasting, love alone is victorious; Love is Moses, Love is Mount Sinai; Love turns mud into Idols and Idols into Gods).

Seat of Urdu

The Nizams made Urdu the official language of Hyderabad State, with the Hyderabad Civil Service operating in Urdu. Osmania University, founded in 1918 by the Seventh Nizam, was India’s first Urdu-medium university, unlike BHU and AMU, which used English. Josh Malihabadi led the Bureau of Translation to modernize Urdu through global texts but was dismissed after writing a critical nazm and later joined India’s freedom struggle. As Rakhshanda Jalil notes, Urdu’s association with Islam and Muslims caused setbacks. Yet, through initiatives like Hindustani Awaaz and Afreen-Afreen, mass participation proves Urdu remains vibrant—deeply cherished in the hearts of many.