ESI losing pulse

31-12-2025 12:30:52 AM

metro india news I hyderabad

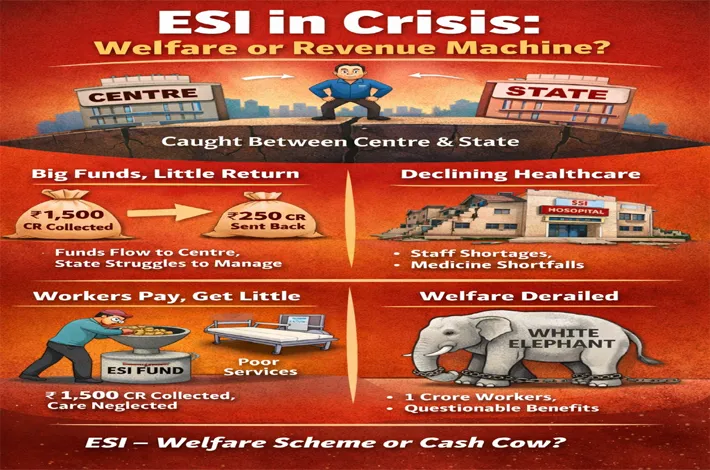

The Employees’ State Insurance (ESI) scheme, meant to provide welfare and healthcare to workers and low-income employees, has today become a case of “all name, no substance”, caught between the Centre and the State. The functioning of ESI in the State is steadily declining as both governments appear to be shifting responsibility onto each other. A system that should safeguard labour welfare is now moving towards stagnation, with medical services weakening day by day.

A close look at ESI services suggests that the system is inching towards paralysis. More concerning is that neither the Centre nor the State is spending even the full amount collected from beneficiaries for their welfare. This has led to doubts over whether the Central government views workers and low-paid employees as beneficiaries or merely as a revenue source. With ESI responsible for providing healthcare to over one crore people in the State, fears are growing that it may soon turn into a white elephant.

As per Central Labour Ministry norms, all employees earning up to Rs 21,000 per month are covered under ESI. Thousands of establishments including small businesses, shops, showrooms, factories, industries and companies fall under the scheme. Currently, around 20 lakh people in the State are ESI beneficiaries. With the Centre reportedly raising the income ceiling to Rs 25,000, another two lakh people are expected to be added.

Including family members, over one crore people — nearly 25 per cent of the State’s population — depend on ESI services.

Every ESI beneficiary contributes monthly along with the employer. From every Rs 100 of wages, Rs 1.75 is deducted from the employee, while the employer contributes Rs 3.50. Assuming an average salary of Rs 12,500, each beneficiary contributes around Rs 218.75 per month, while the employer adds about Rs 437.50. This means nearly Rs 656.25 per beneficiary per month flows to the Central ESI fund. From 20 lakh beneficiaries, this works out to nearly Rs 130 crore per month, or over Rs 1,500 crore annually, collected from the State.

Despite collecting around Rs 1,500 crore every year from the State, the Centre releases only about Rs 250 crore annually. With this limited funding, the State government is expected to manage nearly 70 ESI dispensaries, ESI hospitals in Hyderabad and Warangal, Joint Director offices, the Directorate office near Gandhi Hospital, hospitals at Nacharam and RC Puram, along with staff salaries, pensions, recruitment and overall maintenance. The Rs 250 crore received from the Centre is largely spent on medicines, hospital upkeep and payments to contract employees.

This imbalance has made it increasingly difficult for the State to run ESI facilities effectively. While the Centre continues to collect large contributions, the State is left to shoulder most of the responsibility. As staff recruitment and salary payments are handled by the State, its interest in ESI hospitals and dispensaries is said to be waning. Meanwhile, the Centre directly manages only the ESI hospital and medical college at Erragadda, distancing itself from the rest of the system.

As a result, ESI has turned into a scheme caught between two authorities. Funds flow to the Centre, while the State struggles to maintain hospitals and dispensaries with limited support. Consequently, ESI facilities are being run in a token manner, affecting the quality of medical services available to lakhs of beneficiaries.

Labour groups point out that if the entire Rs 1,500 crore collected annually were spent within the State, super-specialty ESI services could be developed in every district. Instead, the Centre is accused of treating ESI as a revenue-generating mechanism under the cover of welfare, doing little beyond running the Erragadda ESI hospital.

At the same time, the State government is also facing criticism for neglecting the welfare of workers who contribute significantly to economic development. There has been no recruitment of doctors or staff, most pharmacists are expected to retire within the next two years, and essential medicines are often unavailable. With the Centre indifferent and the State seemingly unconcerned, ESI has become a system “caught between two stools”, leaving workers and their families to suffer due to deteriorating healthcare services.

Including family members, over one crore people — nearly 25 per cent of the State’s population — depend on ESI services.

Every ESI beneficiary contributes monthly along with the employer. From every Rs 100 of wages, Rs 1.75 is deducted from the employee, while the employer contributes Rs 3.50. Assuming an average salary of Rs 12,500, each beneficiary contributes around Rs 218.75 per month, while the employer adds about Rs 437.50. This means nearly Rs 656.25 per beneficiary per month flows to the Central ESI fund. From 20 lakh beneficiaries, this works out to nearly Rs 130 crore per month, or over Rs 1,500 crore annually, collected from the State.

Despite collecting around Rs 1,500 crore every year from the State, the Centre releases only about Rs 250 crore annually. With this limited funding, the State government is expected to manage nearly 70 ESI dispensaries, ESI hospitals in Hyderabad and Warangal, Joint Director offices, the Directorate office near Gandhi Hospital, hospitals at Nacharam and RC Puram, along with staff salaries, pensions, recruitment and overall maintenance. The Rs 250 crore received from the Centre is largely spent on medicines, hospital upkeep and payments to contract employees.

This imbalance has made it increasingly difficult for the State to run ESI facilities effectively. While the Centre continues to collect large contributions, the State is left to shoulder most of the responsibility. As staff recruitment and salary payments are handled by the State, its interest in ESI hospitals and dispensaries is said to be waning. Meanwhile, the Centre directly manages only the ESI hospital and medical college at Erragadda, distancing itself from the rest of the system.

As a result, ESI has turned into a scheme caught between two authorities. Funds flow to the Centre, while the State struggles to maintain hospitals and dispensaries with limited support. Consequently, ESI facilities are being run in a token manner, affecting the quality of medical services available to lakhs of beneficiaries.

Labour groups point out that if the entire Rs 1,500 crore collected annually were spent within the State, super-specialty ESI services could be developed in every district. Instead, the Centre is accused of treating ESI as a revenue-generating mechanism under the cover of welfare, doing little beyond running the Erragadda ESI hospital.

At the same time, the State government is also facing criticism for neglecting the welfare of workers who contribute significantly to economic development. There has been no recruitment of doctors or staff, most pharmacists are expected to retire within the next two years, and essential medicines are often unavailable. With the Centre indifferent and the State seemingly unconcerned, ESI has become a system “caught between two stools”, leaving workers and their families to suffer due to deteriorating healthcare services.