HILT or HEIST?

04-12-2025 12:00:00 AM

Who Gains from Hyderabad's Industrial Land Overhaul?

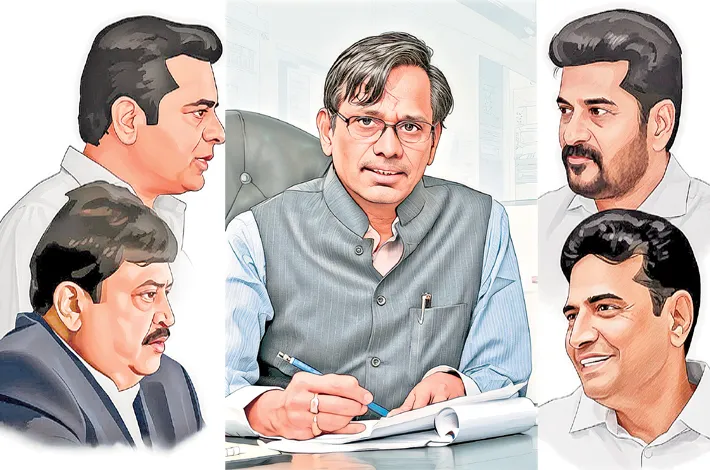

The Telangana government's Hyderabad Industrial Lands Transformation Policy (HILTP), unveiled in November has ignited a firestorm of accusations. Dubbed "HILT" by critics, the policy aims to repurpose nearly 9,300 acres of aging industrial land within the Outer Ring Road (ORR) into vibrant multi-use zones. Proponents hail it as a forward-thinking urban renewal; detractors brand it the "biggest land scam in India's history," with alleged losses to the public exchequer ballooning to Rs5-6 lakh crore. As Bharat Rashtra Samithi (BRS) leader K.T. Rama Rao (KTR) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) spokespersons trade barbs, Chief Minister A Revanth Reddy remains conspicuously silent, while Industries Minister D Sridhar Babu defends it as essential pollution mitigation. But who truly benefits? A deep dive into facts, figures, and ground realities reveals a policy that could enrich a select cadre of landowners at the expense of fiscal prudence and transparency.

The roots of HILT trace back to Hyderabad's post-independence industrial boom. Between 1965 and 1975, successive governments developed 11 key industrial parks spanning approximately 9,292 acres within the ORR, according to a recent Industries and Commerce Department order. These include Kukatpally (1,200 acres), Balanagar (800 acres), Sanathnagar (600 acres), Nacharam (1,000 acres), Uppal (700 acres), Jeedimetla (1,500 acres), and others like Mallapur, Moula Ali, Patancheru (partial), Ramachandrapuram, and Katedan, totaling 4,740 acres of plotted land eligible for immediate conversion. Plots were allotted to industries at nominal rates—often as low as Rs1 lakh per acre—to foster employment and economic growth. Infrastructure like roads, water supply, power grids, and parks was state-funded, turning these zones into self-contained hubs.

After six decades, many units have shuttered or relocated under post-2004 policies incentivizing shifts beyond the ORR, leaving behind polluted, underutilized relics. A 2025 Telangana Industrial Infrastructure Corporation (TGIIC) assessment notes that 70% of these lands now host illegal commercial constructions, with factories repurposed as warehouses or showrooms, rendering them industrially obsolete. Current industrial-use valuations hover at Rs1 crore per acre, hampered by zoning restrictions and environmental hazards like recurring fires and toxic effluents. The policy's genius—or Achilles' heel—lies in its conversion mechanism: A Government Order (GO 27) notifies these lands as "multi-use zones," permitting residential apartments, commercial offices, IT parks, hotels, schools, hospitals, and recreational spaces, aligned with the state's GRID (Growth in Dispersion) urban blueprint.

At its core, HILT mandates a one-time Development Impact Fee (DIF) via the TG-iPASS portal, processed by TGIIC as the nodal agency. Fees are tiered: 30% of Sub-Registrar Office (SRO) guidance value for plots on roads under 80 feet wide, and 50% for wider roads—capped at an average of Rs1 crore per acre, per industry estimates. Post-conversion, market values could skyrocket to Rs40-50 crore per acre in prime spots like Kukatpally or Balanagar, driven by proximity to metro lines and IT corridors. For a typical one-acre plot owner, the math is stark: Pre-HILT cost (industrial valuation + fee) totals Rs2 crore. Post-conversion windfall? A Rs38 crore profit, after fees. Scaled to 9,292 acres, this implies a collective Rs3.53 lakh crore value unlock for private owners—figures eerily close to the user's ground report, though official data pegs plotted areas at 4,740 acres for a more conservative Rs1.9 lakh crore surge.

The government's projected revenue? A modest Rs5,000 crore from DIF collections across 22 parks, including standalone units spanning 2,000 acres. This shortfall fuels scam allegations. KTR, addressing a November 22 press conference, lambasted the policy as a "blueprint for Rs5 lakh crore in kickbacks," claiming SRO rates are already 4-5 times below open-market prices, with only partial collection enabling "politically connected middlemen" to pocket the rest. BJP's A. Maheshwar Reddy upped the ante to Rs6.29 lakh crore on November 24, accusing Revanth Reddy of undervaluing lands to "consolidate Congress influence" via slush funds tied to national high command. Both parties demand suspension, a central agency probe (CBI/ED), and public auctions of 50% of lands, mirroring Mumbai's model. Sridhar Babu counters that similar "freehold" conversions occurred under BRS rule, framing HILT as pollution remediation: "We don't want Hyderabad turning into Delhi," he stated on November 25, emphasizing relocation incentives for polluting units like those in Jeedimetla (150 acres, 102 plotted).

Beneath the rhetoric, ground reports paint a nuanced picture of beneficiaries. Primary winners: Legacy industrialists and benami holders who acquired plots decades ago at throwaway prices. Recent transactions show a spike in purchases—rumors swirl of a six-month "leak" to corporates, with lands snapped up at Rs1-2 crore per acre pre-policy. Industrial associations are reportedly coordinating "smooth transfers" with TGIIC, per anonymous sources. Losers? The exchequer, potentially forfeiting Rs3+ lakh crore in unrealized revenue, and displaced informal workers (estimated 50,000 across parks). Public sentiment, echoed in social media and protests, demands hikes: 50% of market value as fees, 10% built-up area for low-income housing for free of cost and allotment by draw of lots, and penalties on illegal constructions (e.g., Rs10-20 crore per unauthorized building in Uppal). Real estate developers, meanwhile, fret over oversupply—prices in west Hyderabad have dipped 15% due to excess inventory, with HILT's central influx risking further devaluation amid Future City hype.

Is there a conspiracy to defame Sridhar Babu, by some Congress leaders? Whispers suggest yes—BRS's aggressive timeline (applications approved in 45 days) critiques align with past rejections under K. Chandrasekhar Rao's regime, positioning Congress as the "land mafia." Still, no concrete evidence surfaces; Babu's acknowledgment of BRS-era irregularities blunts the attack. Revanth's silence? Strategic, perhaps, as HILT aligns with his "sustainable Hyderabad" vision, but risks alienating voters amid fiscal woes (Telangana's 2025 debt at Rs3.2 lakh crore). The truth? HILT is no outright fraud—it's a pragmatic policy addressing 50-year-old zoning mismatches, backed by GO 27's legal framework. But its fee structure invites graft: A 30% corruption skim on Rs3.53 lakh crore windfall could yield Rs1.06 lakh crore in illicit gains, dwarfing the Rs99,000 crore user's estimate but underscoring opacity risks. To dispel doubts, the government must publish six-month transaction logs, deploy international valuers for market assessments, and impose 10% infrastructure levies on constructions—recovering Rs50,000 crore over a decade.