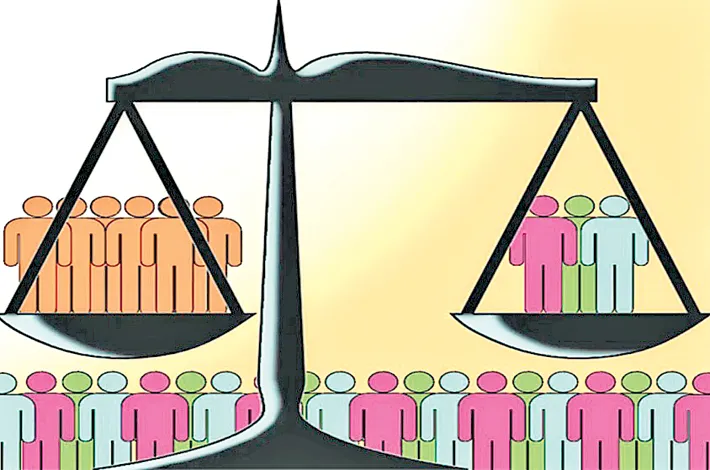

Merit vs Social Justice: Can the Balance Be Found?

10-12-2025 12:00:00 AM

The debate on caste, merit and reservation returned to the spotlight with renewed intensity as a panel of experts examined whether India can truly discuss merit without acknowledging centuries of social inequality. The conversation began with Suraj Milind Yengde, author of Caste Matters, who argued that India’s obsession with merit often ignores the deeper social realities that shape a person’s opportunities. He said that the country continues to use narrow indicators—exam scores, institutional pedigree, and even surnames—to determine merit, while overlooking creativity, lived hardships and structural barriers. According to him, the concept of merit is not inherently flawed; the flaw lies in its selective, exclusionary usage. Unless India first confronts the historical humiliation embedded within caste structures, he said, any debate on merit becomes superficial.

From a grassroots perspective, social activist Gaurav Jaiswal added a dimension that grounded the debate in real-life outcomes. Speaking from a tribal village in Madhya Pradesh, he highlighted how reservation has changed the lives of countless families who had no access to opportunity for generations. He narrated the story of Taruna, who rose from being a student to becoming the sarpanch of her village, and Naven, who secured a job in the Indian Railways after overcoming severe social and economic obstacles. These, he stressed, are not isolated examples but part of a broader wave of first-generation beneficiaries who are now paving the way for their children and younger siblings. For many tribal and Scheduled Caste families, reservation has become the stepping stone to better education, stable employment and political participation. Jaiswal argued that the impact of reservation is visible not only in personal success stories but in shifting the aspirations of entire communities.

Advocate Siddharth Dubey offered a constitutional and historical perspective, reminding the audience that reservation was never designed as a permanent policy but as a necessary corrective to achieve substantive equality. Drawing from Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s interventions in the Constituent Assembly, Dubey said that the goal was to level the playing field—something that could not be accomplished simply by declaring formal equality. He added that while reservation was meant to be reviewed and refined, its purpose remains relevant because caste-based discrimination has evolved rather than disappeared. He also touched upon the introduction of the EWS quota, arguing that while social exclusion must remain central, economic deprivation cannot be ignored either. Yet he cautioned that economic backwardness cannot override or replace caste as a determinant of social discrimination.

Economist Dr. Narendra Jadav deepened the conversation by presenting data-driven insights into how caste discrimination has historically weakened India’s economic potential. He mentioned studies indicating that India’s dramatic fall in global GDP share over centuries can be partially traced to the exclusion of large sections of the population from education and skilled work. By denying equal access to learning and advancement, the country effectively stunted its own growth. Jadav said that reservation has helped reduce long-standing gaps in education and employment, but these disparities remain wide. He referred to subtle forms of discrimination that persist in hiring, workplace treatment and access to opportunities, arguing that the challenge today is not legal inequality but entrenched social attitudes. He called it a “double burden” for marginalised communities—facing both resistance to reservation and inconsistent implementation of policies meant to help them.

As the debate progressed, Suraj Yengde returned with a sharper critique of the resistance to reservation. He argued that much of the opposition stems from discomfort over losing unacknowledged caste privileges that have historically favoured certain communities. He pointed out that over 90 per cent of India’s workforce is employed in the informal sector, where reservation has no application, yet the anger against it often comes from those who continue to benefit from inherited advantages. Yengde said that the real friction begins when individuals from Dalit, Adivasi and OBC communities enter elite institutions or leadership positions, challenging long-standing social hierarchies. The backlash, he suggested, is less about merit and more about fear of losing dominance in these spaces.

Despite the differing viewpoints, the debate concluded with broad agreement that reservation has produced undeniable progress—creating opportunities for millions who were historically excluded. At the same time, the panel acknowledged that the policy must continue evolving to stay effective. They emphasised that any reform should preserve the fundamental purpose of reservation: to ensure fairness, correct historic injustices and create genuine opportunities for those who have long been denied them. The discussion also underlined that societal mindset change must accompany policy measures; without acknowledging caste-based inequalities, India’s conversation on merit will remain incomplete and imbalanced.

The debate made one point clear: India cannot talk about merit without facing the uncomfortable truths of caste. And until those truths are confronted honestly, the question of reservation will continue to stir heated but necessary conversations about justice, equality and the kind of society the country aims to become.