Corporate cash collides with public mandate

24-12-2025 12:00:00 AM

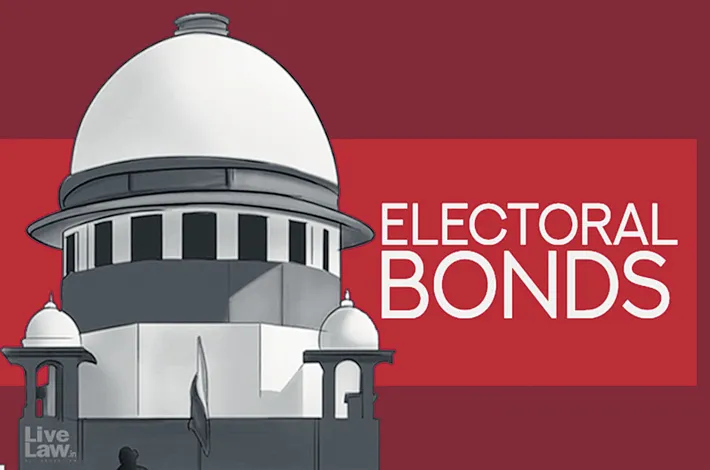

In the first full financial year after the Supreme Court scrapped the controversial electoral bonds scheme, donations channeled through electoral trusts have shot up dramatically, reaching Rs 3,811 crore — more than triple the Rs 1,218 crore recorded the previous year. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the clear frontrunner, pocketing around Rs 3,112-3,143 crore, or over 82% of the total, according to reports submitted to the Election Commission of India (ECI).

In stark contrast, the Congress party received approximately Rs 299 crore, accounting for less than 8% of the total contributions. Regional players, including the Trinamool Congress (TMC) and YSR Congress Party, shared the remaining 10%. Much of this flow has been driven by a handful of powerful electoral trusts. Prudent Electoral Trust, for instance, distributed over Rs 2,668 crore, with Rs 2,181 crore going to the BJP and Rs 216 crore to Congress. Similarly, the Progressive Electoral Trust, associated with the Tata Group, contributed Rs 915 crore, directing Rs 758 crore to BJP and Rs 77 crore to Congress.

This lopsided distribution has reignited debates around fairness and transparency in political financing. Critics argue that the system currently favors parties with stronger corporate networks and incumbent advantages, raising the specter of quid pro quo arrangements where donors might expect contracts or policy favours in return. Congress leaders have voiced concerns that such massive corporate donations to the ruling party undermine the democratic principle of equal opportunity and have suggested reforms linking political funding to parties’ vote shares, claiming this would better reflect actual public support while curbing undue influence.

Congress representatives contend that democracy should not favor inequality. They point to the BJP's dominance in trust donations as proof of an uneven system, arguing that scrapping electoral bonds did little to level the playing field. According to them, despite the Supreme Court ruling, corporate and trust-based funding continues to favor the ruling party disproportionately, highlighting the persistent influence of money in politics.

On the other hand, BJP leaders have defended the inflow of donations as a reflection of public and corporate confidence in their governance and leadership. They assert that donors choose based on a party’s "creditworthiness," track record, and perceived effectiveness rather than any expectation of favours. Party officials have dismissed calls to link donations to vote shares as unrealistic, emphasizing that contributions are voluntary and should remain so. “Donations are willful contributions, not a tax or enforced allocation,” they maintain, while welcoming any transparent reforms agreed upon by all stakeholders.

Experts and civil society voices, however, caution that the debate touches upon broader systemic issues. A noted psephologist pointed out that while electoral trusts provide a layer of traceability, a true reform would involve exploring state funding of elections, similar to models in countries like Germany, where public money is distributed proportionally based on prior election results. However, he warned that linking voluntary corporate donations to vote shares could undermine donor freedom and reduce the role of private funding in supporting political engagement.

The Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) has long highlighted the risks inherent in political financing, describing it as a "fountainhead of corruption" globally. A senior ADR office bearer noted multiple flaws in the current system, including the absence of limits on receipts or spending by parties, the potential for black money through cash donations under reporting thresholds, and incomplete transparency within electoral trusts, where allocation decisions are made internally by trust boards. He suggested that reforms should include capping party expenditures, digitizing all transactions for full traceability, and ultimately moving toward taxpayer-funded elections with stringent safeguards.

Electoral trusts were originally introduced under the 2013 scheme to channel corporate donations more transparently. They are required to distribute at least 95% of contributions to eligible political parties while maintaining audited accounts submitted to the ECI and tax authorities. Cash donations are prohibited, and the mechanism was intended to reduce unaccounted money in politics. Despite these safeguards, critics argue that corporates naturally gravitate toward parties in power at the Centre or in influential states. After the Supreme Court’s 2024 ruling against electoral bonds, trusts have largely filled the funding gap, but the disproportionate advantage enjoyed by the BJP — buoyed by its third term at the Centre and strong state performances — has intensified opposition concerns.

The scale of funding disparities is striking. In FY 2024-25, the BJP’s total political donations, including sources outside trusts, exceeded Rs 6,000 crore, compared to Congress’s Rs 522 crore. This stark contrast has amplified calls for comprehensive reforms, including full disclosure of donors, caps on party spending, and exploring partial or full state funding of elections. Yet, political consensus remains elusive, as parties debate the balance between donor freedom and electoral fairness.

The situation underscores a core democratic tension: how to maintain the independence and voluntary nature of political donations while ensuring that no party enjoys an unfair advantage purely due to financial muscle. Critics worry that unchecked corporate influence could erode public trust in elections, while proponents argue that robust funding reflects confidence in governance. The challenge lies in finding mechanisms that maintain transparency, encourage fair competition, and prevent corruption without stifling voluntary political support.

In conclusion, the post-electoral bond era has highlighted the persistent role of money in shaping political outcomes in India. While electoral trusts offer improved transparency, the massive advantage enjoyed by the BJP has reignited debates over fairness, accountability, and the potential for systemic reforms. As discussions continue, proposals like linking state funding to prior vote shares, imposing expenditure limits, and digitizing donations are gaining traction, reflecting the growing consensus that political financing needs urgent, thoughtful reform to strengthen democratic processes in the country.