Echoes by the Musi

27-10-2025 12:00:00 AM

Mir sat on the crumbling steps of his ancestral home, watching the Musi River flow sluggishly under the morning haze. The river had grown tired, much like him—its waters no longer sparkled or sang the songs he once heard as a boy. The banks were lined with concrete now, and where old tamarind trees had once bowed into the water, glass buildings stood upright and indifferent.

He was seventy, though he often said age didn’t matter; it was the world that had grown older, not him. Yet the ache in his knees and the tremor in his fingers reminded him of time’s quiet mockery. He carried a leather notebook wherever he went—a relic of his youth when he had dreamed of being a poet, one whose verses could stir the air like fragrance from an ittar bottle.

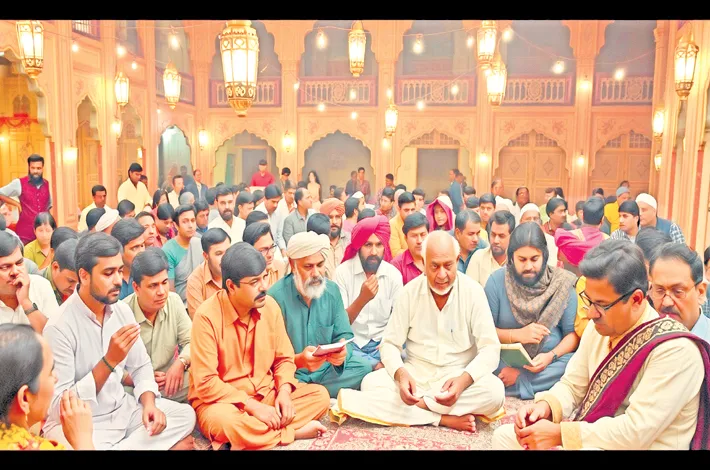

Every evening, Mir would sit by the river, writing fragments of memory—half poems, half sighs. He wrote about mehfils where lamps flickered like fireflies, and poets recited shayari till midnight. He remembered how words once had weight, how silence between two lines carried meaning deeper than speech. Now, when he overheard conversations in cafés, they were clipped, hurried, typed with thumbs instead of spoken with breath.

In the 1960s, Hyderabad had been slower, more tender. The bazaars smelled of jasmine and roasted coffee. The evenings were for listening—to ghazals, to the azan drifting through alleys, to the rhythm of the city’s heart. His father would take him to the mushaira in Abids, where poets debated like philosophers and laughed like children.

Mir smiled faintly remembering one such night—how his father, tall and dignified in his white kurta, had whispered, “Beta, words are not to impress. They are to feel.”

He had held on to that sentence all his life.

Now, the world seemed to have no time to feel. His grandchildren lived abroad, speaking in a language that didn’t bend like Urdu, didn’t sigh the way Urdu did. His son, a banker, visited him once a month, always in a hurry, always checking his phone. “Abba, you should move in with us,” he’d insist. “This place is falling apart.”

Mir would smile and say, “So am I. Let the house and I fall together.”

Each morning, he brewed tea the old way—slowly. The water simmered before the leaves were added. The steam carried the scent of time itself. He’d pour it into a chipped cup, sit by the window, and listen to the distant city roar. The world outside rushed as if afraid to stop.

Sometimes, young people from the neighborhood would come by, curious about the old man who wrote Urdu poetry in an age of Instagram quotes. They called him Mir Saab. They’d sit with him for a while, but their attention would wander. When he recited a couplet, their phones would glow.

“Read that again, Mir Saab,” one had said once. “I’ll record it for my YouTube channel.”

He had smiled politely, but inside, something wilted. The poetry that was meant to live between hearts was now trapped in screens.

That evening, as twilight softened the sky, Mir walked to the river again. He watched the faint reflection of the city lights tremble in the dark water. The Musi had seen everything—the Qutb Shahi tombs, the floods, the bridges, the city’s swelling appetite. And now, it watched Mir, the last listener to its stories.

He opened his notebook. The pages fluttered in the breeze, as if eager to escape. He began to write—not about the past this time, but about what remained.

“Even as the river forgets its own songs, A single wave remembers the shore.”

He paused, listening to the hum of motorcycles, the honking, the faraway strains of a film song. Somewhere beyond that noise, he thought he could still hear the faint echo of a sitar.

When night fell, Mir didn’t light the lamp. He liked the darkness—it reminded him of the candlelit rooms of his youth. He imagined his father again, imagined the poets and lovers and dreamers who once filled this city with verse. He felt them sitting beside him, whispering through the rustle of leaves, the flow of the river, the gentle ticking of time.

The next morning, when his neighbor came to deliver milk, Mir’s chair was empty. His notebook lay open on the table, a half-written poem waiting for its last line.

The Musi flowed quietly outside, as if carrying his unfinished words downstream. And though the city would go on rushing, somewhere in its heart, the echoes of Mir’s verses would linger—soft, unhurried, and eternal.

“Zindagi guzri hai lafzon ke saaye mein, Ab khamoshi bhi ek nazm lagti hai.”

(I have lived in the shade of words—Now even silence feels like a poem.)