How the US controls regimes strategically the world over

19-09-2025 12:00:00 AM

For decades, the US has reshaped govts to serve its strategic interests. India must understand these patterns to protect its sovereignty

For much of the post-war era, the United States has cloaked its foreign policy in the rhetoric of liberty, democracy, and human rights. Yet, the historical record points to something more of less flattering: a practice of regime change, pursued whenever a government’s orientation diverged from Washington’s strategic or economic preferences.

From the overthrow of Iran’s Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953 to the ousting of Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973, from the invasion of Iraq to the dismemberment of Libya, the pattern is unmistakable. The US has been far from being the champion of democracy.

This is not a defence of authoritarian regimes or despotic rulers. The consequences of the US interventions have often been destabilising and insensitive to the local population. The coup in Tehran sowed the seeds for the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The removal of Saddam Hussein fractured Iraq, unleashing sectarian violence and giving rise to the Islamic State. Libya, once a functioning state, was reduced to an arena of militias and external patrons. Venezuela remains trapped in a spiral of sanctions and polarisation.

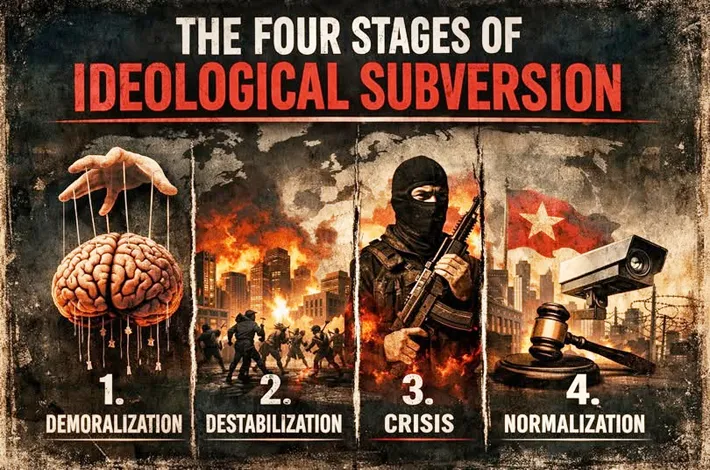

Even where Washington has not deployed troops, its repertoire has included covert funding of opposition groups, the weaponisation of media, crippling sanctions, and the legitimisation of coups with high-minded rhetoric. The inconsistency is glaring.The scale of American interventions shows that this is no aberration. Between 1991 and 2022 alone, the US mounted over 250 military interventions worldwide, many aimed at reshaping political orders.

South Asia offers recent illustrations. The sudden political transition in Bangladesh unfolded at India’s doorstep. Pakistan’s hand in shaping that outcome was evident, seemingly with American acquiescence. The Pahalgam incident further highlighted how emboldened Islamabad has become once it sensed tacit support. Afghanistan tells a similar story. With Pakistan’s facilitation, the US engineered the fall of Kabul. But when the Taliban slipped from Islamabad’s control, Washington designated them as terrorists. Each episode underscores a consistent point: the Indian influence in its own neighbourhood is checked whenever it appears to gain traction.

The larger pattern is familiar. Against China, the US mobilises Taiwan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Vietnam as levers of pressure. India, too, is courted as a “strategic ally” primarily to balance Beijing. Beyond that, Washington’s interest in India is circumscribed. It is not inconceivable that, in time, American firms will be nudged to diversify supply chains away not only from China but also from India, shifting manufacturing to Southeast Asia.

The US has increasingly weaponised technology access as an instrument of strategic influence. Restrictions on semiconductor exports, defence technologies, and emerging domains like artificial intelligence serve not merely as trade measures but as levers to shape the policies of other nations. For India, dependence on critical technologies exposes vulnerabilities that Washington can exploit to constrain both economic and defence autonomy. Recognising the slow pace of indigenous capability development, particularly in AI and quantum computing, New Delhi must urgently accelerate investment and funding to reclaim lost ground and reduce dependence on external pressures.

Financial instruments have long been another axis of the American influence. The dominance of the dollar allows Washington to isolate states from the global economy with targeted or even secondary sanctions, as seen in Iran, Russia, and Venezuela. Even India has had to navigate risks associated with energy imports and defence procurements, underscoring the subtle yet profound ways that financial control can serve as a tool of geopolitical leverage. Efforts to promote trade in local currencies and explore alternatives to dollar-based transactions are a manifestation of a strategic hedging imperative.

India’s position in global security architecture further shapes its exposure to American influence. While initiatives such as the QUAD present India as a “strategic partner”, New Delhi has carefully avoided treaty obligations that would compromise autonomy. The United States may frame such partnerships as alliances, but India’s policy reflects a conscious preservation of independent decision-making, demonstrating that engagement need not translate into subordination.

Even climate and energy policies have become vehicles for exerting influence under the guise of global responsibility. Carbon border adjustments, trade-linked environmental standards, and conditionalities embedded in climate diplomacy create pressures that can reshape domestic policy in targeted states. For India, these represent a new front in which sovereignty can be indirectly contested, requiring the nation to balance environmental commitments with the imperatives of national development and strategic autonomy.

Assertions by President Trump that he had “brokered” the ceasefire between India and Pakistan, despite India’s denial of the same, signifies that the US seeks to force-fit its preferred narrative onto the world, regardless of the facts on the ground or the sovereign positions of other states.

Economic coercion is another facet of American influence. The Trump administration’s tariffs against China, India, and even Europe were not merely about trade balances. They were a lever of pressure intended to force governments into domestic policy shifts that favoured US calculations.

Equally, India has shown that it will not be reduced to a vassal. New Delhi has stood firm against the American pressure to open its agriculture, dairy, and fisheries markets during trade negotiations, recognising the existential stakes for millions of its citizens. Nor has it abandoned its long-standing partnership with Russia, a relationship rooted in decades of defence and energy cooperation, despite sustained Western exhortations in the wake of Ukraine. These choices underline a central point: India will engage the United States as a partner but never as a patron. Its strategic autonomy is not negotiable.

For India, the lessons are stark. Whether in Nepal, Bangladesh, or Afghanistan, our influence has been blunted whenever it clashed with Washington’s calculus. In West Asia, the asymmetry is just as apparent. Israel’s recent actions in Qatar are tolerated, even as they destabilise the region. History shows that while toppling regimes may be simple for a superpower, controlling outcomes is far more elusive. That is why regime change remains one of the most hazardous instruments of statecraft.

The harsh truth is this: the United States does not so much support democracies as it wants to control them. In India, regime change is not easily executed. That is precisely why other methods, including economic pressure, neighbourhood manipulation, and diplomatic constraints, are likely to intensify. For New Delhi, the only credible safeguard lies in strategic vigilance and the defence of genuine autonomy.