The politics of freebies

23-02-2026 12:00:00 AM

Freebies are undoubtedly taking a toll on the fiscal health of the State and election promises resulting in empty treasuries

The Freebie Dilemma

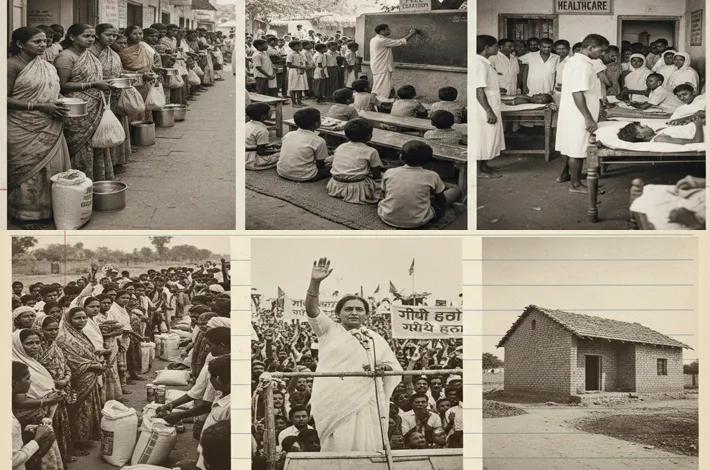

1950

Introduction of Ration System, Free Education, and Free Healthcare

1971

Garibi Hatao Programme

1982

Free Mid-Day Meal Scheme

1983

Rs. 2 per kg Rice Scheme

2006

Distribution of Free TVs and Laptops

2014

Introduction of Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT)

2018

Cash Assistance Schemes for Farmers

2020

Free Travel for Women and Expansion of Free Electricity

metro india news I hyderabad

The debate over “freebies” has once again moved to the centre of Indian politics. While governments argue that welfare schemes are transforming the lives of the poor, critics warn that such promises are placing an unsustainable burden on state finances. With the Supreme Court recently making key observations on the issue, a nationwide discussion has intensified on whether these schemes are genuine welfare measures or long-term fiscal risks.

From free electricity and bus travel to farm subsidies and direct cash transfers, welfare initiatives have expanded across sectors. The key question remains: are these schemes empowering the poor, or are they pushing states towards financial stress?

In the decades following Independence, welfare measures were introduced to tackle poverty, unemployment and food shortages. The public distribution system, fertilizer subsidies for farmers, and government support in education and healthcare were viewed as welfare interventions rather than outright freebies. During the 1970s and 1980s, poverty eradication became central to political discourse, with programmes like “Garibi Hatao” strengthening direct economic assistance to citizens. Subsidized power and irrigation for farmers and rural development initiatives gained prominence.

By the 1980s and 1990s, welfare measures increasingly became electoral tools, particularly in southern states. Tamil Nadu’s introduction of the free midday meal scheme in 1980 significantly improved school enrolment among poor children and later expanded nationwide. After 2000, freebies became a dominant election agenda, with states offering free televisions, electricity, laptops, and large-scale cash transfers. Since 2010, technological advancements have reshaped welfare delivery through direct benefit transfers into bank accounts, Aadhaar-linked schemes, and targeted cash support to farmers, women and students.

In undivided Andhra Pradesh, the politics of welfare took firm root in the 1980s. The Rs. 2 per kg rice scheme introduced during that period created a political shift, enhancing food security for the poor and demonstrating that welfare could influence electoral outcomes. From 2004 onwards, free electricity for farmers, fee reimbursement for students, subsidized rice schemes and large-scale public health initiatives expanded significantly. These measures improved living standards and access to education and healthcare, but also led to rising expenditure and fiscal pressure.

After Telangana was formed in 2014, welfare policies took a new shape with direct cash transfers becoming central to governance. Schemes such as Rythu Bandhu for farm investment support, Rythu Bima insurance, Asara pensions for the elderly and differently-abled, Kalyana Lakshmi and Shaadi Mubarak assistance, and free power for farmers became flagship programmes.

These initiatives boosted rural incomes and provided relief to economically weaker sections. However, financial reports have indicated that the expanding welfare outlay has added significant strain on the state treasury, increasing debt levels and limiting funds for development projects.

Criticism has also emerged over unfulfilled or partially implemented promises. In Telangana, several commitments announced during elections have faced delays or limited rollout. The promise of Rs. 3,000 monthly unemployment allowance to every jobless youth has not materialized.

Large-scale construction of double-bedroom houses has not been fully completed. Free laptops for government school students and universal free education from KG to PG have seen partial implementation. Farm loan waivers were carried out in phases, benefiting some farmers but drawing criticism over incomplete coverage. Financial constraints, limited revenue, identification challenges, and administrative hurdles have been cited as reasons.

The 2023 Telangana Assembly elections revolved heavily around welfare guarantees. Major political parties announced extensive cash transfers and subsidies. Free RTC bus travel for women has been implemented state-wide. However, certain promised schemes such as Rs. 2,500 monthly assistance under the Mahalaxmi programme and Rs. 15,000 per acre annual support under Rythu Bharosa have faced implementation concerns.

Subsidized gas cylinders at Rs. 500 and 200 units of free electricity for poor households are in operation, while unemployment assistance under youth development schemes has not commenced. During the previous decade, welfare schemes such as Rythu Bandhu, Rythu Bima, Asara pensions, Kalyana Lakshmi and Shaadi Mubarak were widely implemented, though promises like unemployment allowances and universal double-bedroom housing did not fully meet targets.

Political analysts argue that welfare, once designed as social support, has increasingly become an electoral strategy. Parties often compete to outbid each other with more attractive promises, leading to escalating commitments. While such schemes influence voters, especially among poor and middle-class groups, concerns remain over delayed or partial implementation after elections. The competition has transformed welfare into a political battleground.

Experts stress that transparency and fiscal responsibility are crucial. Expanding welfare budgets can crowd out funds for infrastructure and development projects. Continuous expansion of freebies risks mounting public debt. The Supreme Court has observed that governments must responsibly use public funds and assess the financial impact of welfare commitments. While welfare remains essential, economists argue it should be designed to promote self-reliance, employment generation, industrial growth, education and skill development. Without transparency and long-term fiscal planning, short-term electoral gains could translate into economic burdens for future generations.