Tumhari ye duniya badalni hai… badalni hai… badalni hai…”

11-12-2025 12:00:00 AM

(“This world of yours has to be changed… has to be changed… has to be changed…”).

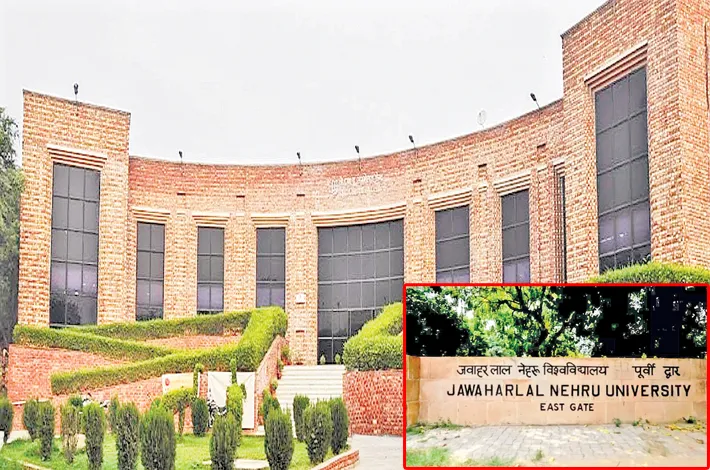

Kavi Vidrohi, born Ramashankar Yadav on December 3, 1957, in Sultanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India, to peasant parents Ramnarayan Yadav and Karma Devi, was a renowned Hindi poet, revolutionary, and social activist. Married young to Shanti Devi, he pursued postgraduate studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in the 1980s but was rusticated twice for his involvement in Leftist student politics and protests, eventually making the campus his lifelong home despite never completing his degree.

Known as the "rebel poet" or "people's bard," Vidrohi wielded poetry as a weapon against state repression, caste discrimination, gender inequality, religious superstition, and the persecution of marginalized communities. He recited fiery verses orally at JNU demonstrations, earning acclaim for works like Nayi Kheti (his only published collection, 2011) and poems such as "Mohenjodaro" and "Auratein," which critiqued patriarchal violence and societal ruins. A 2011 documentary, Main Tumhara Kavi Hoon (I Am Your Poet), captured his nomadic, idealistic life on the margins.

Vidrohi passed away on December 8, 2015, at age 58. In his honor, JNU students renamed the Students' Union building after him, immortalizing his rebellious spirit.Kavi Vidrohi lived one of the most unconventional and deliberately austere lives among modern Hindi poets. For almost 35 years (from the early 1980s until his death in 2015), he made Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) campus in Delhi his permanent home, but without ever owning a room, house, or any fixed address.

Here is how he actually lived:

No fixed shelter: He slept wherever he found space—on footpaths, under trees, in dhabas (tea stalls), inside the 24-hour Ganga Dhaba, on the steps of the library, or on the floor of friends’ hostel rooms. In later years he often slept on a stone bench outside the JNU Students’ Union office or in the open courtyard of the Administrative Block.

No possessions: He owned almost nothing—just one pair of kurta-pajama (often torn and patched), a jhola (cloth bag) containing a few notebooks, a pen, and sometimes a blanket in winter. He refused to own money, a phone, a watch, or even a toothbrush for long periods.

Food: He ate whatever students or dhaba owners offered him—roti-sabzi, tea, biscuits, sometimes nothing for a whole day. He never asked, but people fed him because they loved his poetry. When someone forced money on him, he immediately distributed it to beggars or other needy people. No job, no income: He never took salaried work, never applied for any government or academic post, and refused most invitations to become a “professional” poet at literary festivals that paid honorariums. Poetry and revolution were his only “work.”

Daily routine: He wandered the campus from morning to late night, sitting in on protests, reciting new poems spontaneously, debating with students, and writing in his notebooks under streetlights. At night he would recite to whoever was willing to listen until 2–3 a.m.

Health and hygiene: He rarely bathed regularly, cut his hair only when students forcibly took him to a barber, and refused medical treatment even when seriously ill. In his last years he suffered from tuberculosis and liver ailments but continued living outdoors.

Family: After coming to JNU he almost completely cut off contact with his wife and children in the village. He believed that a true revolutionary could not have domestic attachments.

This extreme, almost ascetic rejection of material life was deliberate—he called it his protest against a consumerist and unjust society. Students nicknamed the area around Ganga Dhaba “Vidrohi Chowk” because that was his open-air durbar.When he died on 8 December 2015 of liver failure, his body was found on the same stone bench outside the Administrative Block where he had slept for decades. He was cremated the next day with thousands of students chanting his own lines:

“Tumhari ye duniya badalni hai… badalni hai… badalni hai…”

(“This world of yours has to be changed… has to be changed… has to be changed…”).