Did spiritual grace shape a cinematic legend?

31-12-2025 12:00:00 AM

The silent force behind Chittoor V. Nagaiah’s journey

December 30 carries an unusual resonance in India’s cultural and spiritual calendar. It marks the English birth anniversary of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi and also the death anniversary of legendary actor, singer, director and producer Chittoor V. Nagaiah. Fifty-two years after Nagaiah’s passing, the coincidence of the date raises a compelling question that still invites debate: was his rise in cinema the result of talent alone, or was it shaped by an unseen spiritual hand?

At a superficial level, the life paths of a Supreme Jnani rooted in silence and self-realisation, and a film thespian immersed in performance and public adulation, appear worlds apart. Yet Nagaiah’s own life story suggests that these two seemingly opposite worlds intersected in a way that profoundly altered his destiny.

Born in 1904 in Chittoor, in present-day Andhra Pradesh, V. Nagaiah’s early years were marked not by success but by intense personal tragedy. Married young, he lost his first wife soon after she gave birth to a daughter. Overcome with grief, Nagaiah struggled to steady himself and was encouraged by friends to take up music concerts, recognising his strong grounding in classical music. Life, however, dealt him further blows. His second wife died due to complications following a miscarriage, and his daughter from the first marriage later passed away after a brief illness. With his family wiped out and his inner world shattered, Nagaiah found no comfort in material life. In a moment of despair, he left home and began wandering without purpose.

In the early 1930s, his journey led him to Ramanasramam in Tiruvannamalai, the abode of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi. What followed would later be described by Nagaiah as a turning point that saved him from complete emotional collapse. He spoke of the ashram as a space of profound peace, where the very atmosphere seemed to quieten his tormented mind. He later recalled that the majestic silence of Bhagavan ended his suffering and eased his obsessive grief over repeated bereavements. Interestingly, Nagaiah never engaged in any extended conversation with the Maharshi. Yet he felt an unspoken bond, a quiet sense of being understood and held, without words being exchanged.

During this period, Nagaiah became close to Paul Brunton, the British writer who was then staying near the ashram. Brunton would later author A Search in Secret India, a book that played a crucial role in introducing Ramana Maharshi to the Western world. For Nagaiah, days passed in contentment and inner stillness at Ramanasramam, far removed from ambition, applause or financial security.

This calm was disrupted when a friend from Chittoor happened to spot him at the ashram and urged him to take up a recording assignment for a film project. Nagaiah found himself torn. The peace he had discovered seemed incompatible with a return to the world he had renounced. He resolved that he would accept the offer only if Bhagavan permitted it. When he finally sought the Maharshi’s consent, the reply was brief but striking: yes, you can go, there is still a lot of work for you to do. Nagaiah later admitted that he could not comprehend the meaning of those words at the time. Yet that single sentence pushed him back into the world, setting him on a path that would define South Indian cinema for decades.

What followed was a remarkable transformation. Nagaiah entered the film industry and soon earned acclaim for his depth, restraint and spiritual intensity on screen. His performances in films such as Potana and Thyagayya, where he portrayed the great Telugu poet and the saint-composer Tyagaraja respectively, are still regarded as milestones. Thyagayya, in particular, remains a musical masterpiece that fused devotion, art and cinema. Nagaiah went on to act in numerous Telugu and Tamil films, often playing elderly patriarchs, sages and morally upright figures. Beyond acting, he contributed as a singer, music composer and director, shaping the cultural tone of an era.

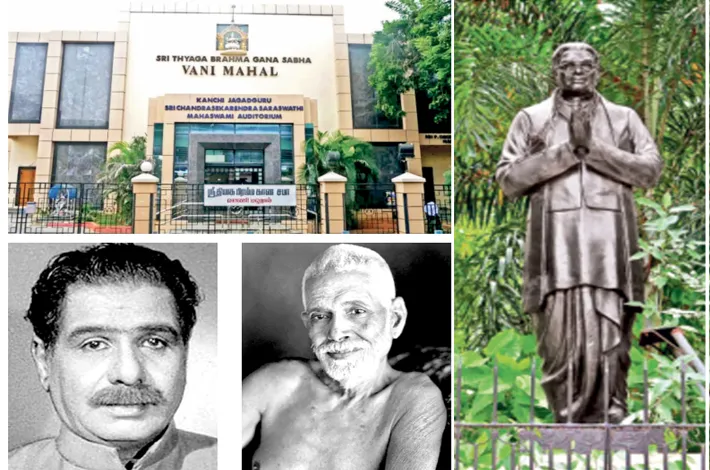

Despite fame and recognition, Nagaiah lived with striking detachment from wealth. A revealing incident from the 1940s illustrates this. Returning from a Carnatic concert by G.N. Balasubramaniam in Mylapore on a rainy evening, he noticed rasikas walking long distances to T. Nagar and Mambalam. Disturbed by this, Nagaiah repeatedly drove them home in his car, making several trips through the night. The incident planted a larger idea in his mind. Soon after, he worked towards establishing a cultural sabha and an auditorium in T. Nagar. This effort led to the birth of the Thyaga Brahma Gana Sabha and the construction of Vani Mahal on G.N. Chetty Road, a space that would become central to Chennai’s classical music scene. The Sabha was named by Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar himself. At Nagaiah’s home, it was common for nearly fifty people to be fed every day. He gave freely, without thought for savings or future security.

Ironically, this lack of material caution caught up with him in later years. By the 1960s, when he was well past 65, Nagaiah was forced to accept minor and insignificant roles simply to survive. When writer and lawyer Randor Guy once expressed pain at seeing him in such circumstances, Nagaiah responded with philosophical calm, quoting the Sanskrit saying that one must assume many roles for the sake of the stomach. To many devotees, this phase was seen not as misfortune, but as the final burning away of karma.

Today, a statue of Chittoor V. Nagaiah stands near Panagal Park in T. Nagar, overlooking a city whose cultural life he helped shape. Nagaiah himself once reflected that he would have withered away, unhonoured and unsung, but for the grace of Bhagavan Ramana, who poured new life into him and guided him along the path best suited to his nature. Decades after his death, the question still lingers in public memory: was Nagaiah merely an artist shaped by circumstance, or a seeker gently pushed back into the world to complete unfinished work?