Disappearing family doctors leave growing gap in healthcare

08-02-2026 12:00:00 AM

HEMA SINGULURI | Hyderabad

Why is healthcare system at a crossroads? The answer to a great extent lies in the disappearance of the family doctor. He was the first point of contact and knew every family member. Family doctors understood generations, social contexts, and local health needs, offering rational and personalized care. Studies globally show that strong primary care systems improve health outcomes, reduce costs, and ensure equity. Nearly 70–80% of health problems can be managed effectively at the family physician level. Yet, India disproportionately invests in tertiary care while allowing primary care to wither.

Dr. Gattu Srinivasulu, past Vice President of IMA Telangana state and practicing family physician at Shreeshaa Clinic, explained, “India’s healthcare crisis is not happening in intensive care units or corporate hospitals. It is happening quietly, tragically, at the disappearing habitat of the family physician. Hospitals cannot replace clinics. Specialists cannot replace family physicians. Technology cannot replace trust.”

Regulation is Pushing Clinics to the Edge

One of the main reasons clinics are vanishing is regulatory pressure. The Clinical Establishments Act (CEA), intended to standardize healthcare, has become a blunt instrument. “A solo practitioner faces the same compliance framework as a multi-specialty hospital,” Dr. Srinivasulu said. “Registers, renewals, inspections, and infrastructure mandates consume time, money, and morale. Instead of enabling care, it creates fear, compliance fatigue, and forces young doctors into salaried jobs or non-clinical careers.”

The result is a dangerous vacuum. While qualified doctors struggle under rules, quacks operate freely, unregistered, unmonitored, and accountable to no one. They undercut prices, misuse drugs, and cause preventable harm, yet the medical profession is blamed when things go wrong. “Over-regulating qualified doctors while under-policing quacks is unethical and unsafe,” adds Dr. Srinivasulu.

India produces specialists, but family physicians are neglected. Departments of Family Medicine exist on paper, career pathways remain unclear, and social respect is eroding. “Yet in rural and semi-urban India, the family physician is the most accessible, affordable, and acceptable provider,” Dr. Srinivasulu noted. Undermining them is equivalent to dismantling the nation’s health security.

Dr. Srinivasulu emphasizes, “Healthcare does not begin in hospitals. It begins in clinics, in conversations, in continuity. Protect the family physician. Strengthen the clinic. Heal the system.”

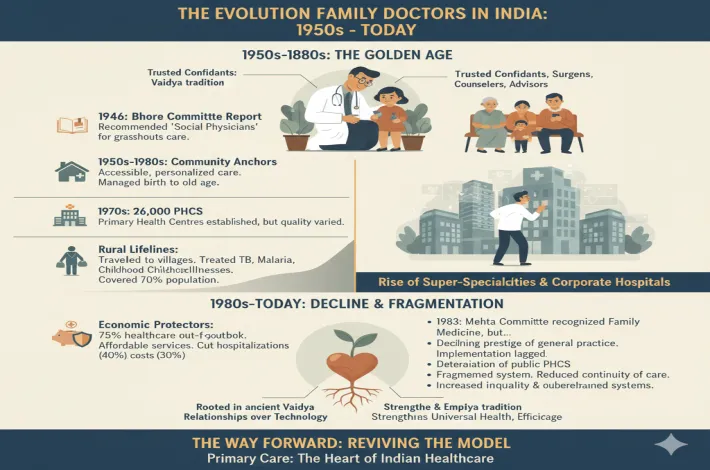

Evolution of family doctors

In the 1960s, the family doctor was an integral part of almost every household. These doctors knew families across generations—their medical histories, habits, and hereditary conditions. A visit for asthma would prompt the doctor to recall similar problems among maternal relatives; a complaint of hair loss might be linked to a grandmother’s history. Family doctors were trusted confidants, often seen as physicians, surgeons, counselors and advisors rolled into one. Today, the near disappearance of this model is both sad and concerning.

Rooted in ancient traditions, the concept of the family physician—known as the Vaidya in classical times—became a cornerstone of India’s healthcare system in the decades following Independence. From the 1950s to the 1980s, family doctors served as community anchors, delivering accessible and personalized care long before super-specialties and corporate hospitals dominated healthcare.

Post-Independence reforms shaped this role further. The landmark Bhore Committee Report of 1946 recommended “social physicians” to provide preventive and curative services at the grassroots level. These generalists were intended to form the backbone of Primary Health Centres (PHCs). By the 1970s, India had nearly 26,000 PHCs, but limited infrastructure and uneven quality meant that many citizens relied on private family doctors operating from modest clinics, especially in urban and semi-urban areas.

Family doctors offered continuity of care unmatched by today’s fragmented system. They followed patients from birth to old age, managing vaccinations, infections, maternal care, and chronic illnesses. In rural India—home to over 70% of the population—they were lifelines, traveling to remote villages to treat tuberculosis, malaria, and childhood illnesses. National Sample Survey data from the period showed that lifestyle diseases, maternal health, and child care dominated healthcare needs—areas well managed at the primary level.

Economically, family doctors were vital. With over 75% of healthcare spending out-of-pocket in the 1970s and 1980s, their affordable services protected families from financial distress. Trained largely through the MBBS system influenced by the Bhore Committee, they required less investment than specialists while reducing unnecessary hospital admissions. International comparisons suggested strong primary care could cut hospitalizations by up to 40% and overall costs by 30%.

However, challenges emerged. Although the Mehta Committee (1983) recognized family medicine as a specialty, implementation lagged. The rise of specialization, declining prestige of general practice, and deterioration of public PHCs led to their gradual marginalization.

Despite this decline, family doctors once represented the heart of Indian healthcare—accessible, empathetic and efficient. In today’s context of inequality and overburdened systems, reviving this model could strengthen universal health coverage. The legacy of the Vaidya reminds us that lasting healing begins with relationships, not technology alone.