From crisis to crossroads: Comparision of two countries

07-12-2025 12:00:00 AM

India's aviation sector, once a symbol of liberalization, now mirrors broader economic monopolies. Oligarchs in telecom (Reliance Jio) and retail (Reliance Retail) dominate, stifling innovation and consumer choice

In the sweltering chaos of India's airports this December, a stark reminder of governance gaps unfolded. IndiGo, the country's dominant low-cost carrier controlling over 60% of domestic air traffic, unleashed pandemonium by cancelling more than 1,000 flights in a single day on December 5, 2025.Stranded passengers wept at counters in Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru, airfares surged, and the nation's aviation backbone buckled under the weight of new pilot rest regulations. The government's response?

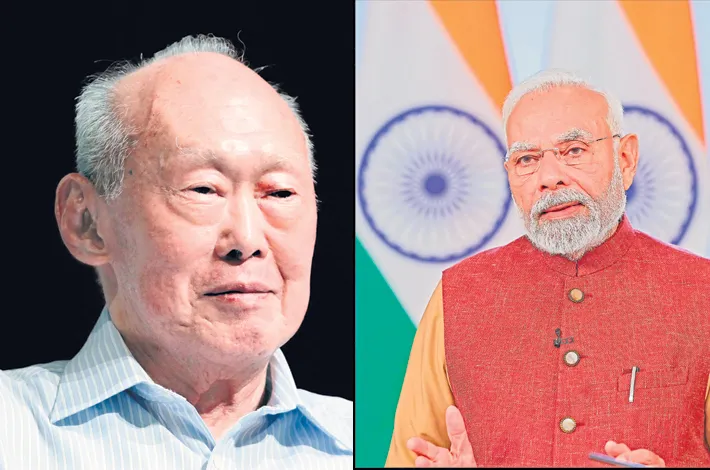

A swift exemption from those very rules until February 2026, effectively handing victory to the monopoly. This capitulation drew sharp online rebuke, including a viral X post by political commentator Gaurav Pandhi, who juxtaposed it against Singapore's legendary leader Lee Kuan Yew's unyielding stance during a 1980s airline crisis. "Modi and the BJP simply don’t have the stomach to confront monopolies," Pandhi tweeted, attaching footage of Lee Hsien Loong, Yew's successor, embodying Singapore's no-nonsense ethos.

As 2025 draws to a close, this incident crystallizes a deeper divergence between two Asian powerhouses: Singapore, the disciplined city-state that transformed from a resource-poor backwater into a global paragon, and India, the booming democracy with much higher potential for excellence than Singapore, yet battling institutional inertia. Both nations emerged from colonial shadows—Singapore in 1965, India in 1947—yet their trajectories diverge dramatically in economy, governance, and quality of life. Drawing on the IndiGo saga as a lens, this article explores these contrasts, revealing what Singapore's model offers a resurgent India.

The Indigo meltdown: Monopoly grips on Indian skies

The crisis erupted mid-week in early December 2025, triggered by the Directorate General of Civil Aviation's (DGCA) enforcement of stricter Flight Duty Time Limitations (FDTL). These rules mandated longer rest for pilots and curbed nighttime flying, aimed at curbing fatigue-related incidents. IndiGo, ill-prepared with a thin crew roster post-COVID expansions, responded by slashing schedules. By Friday, all departures from Delhi's Indira Gandhi International Airport—India's busiest hub—were grounded, affecting tens of thousands. Chaos ensued: families missed funerals, business deals crumbled, and alternative carriers like Air India hiked fares by 200% on opportunistic routes.

India's aviation sector, once a symbol of liberalization, now mirrors broader economic monopolies. Oligarchs in telecom (Reliance Jio) and retail (Reliance Retail) dominate, stifling innovation and consumer choice. The government's reluctance to wield antitrust tools—despite a revamped Competition Commission—originates from a growth-at-all-costs mantra. In 2025, India's GDP hit $4.1 trillion, overtaking Japan for fourth place globally, with 6.5% growth driven by digital services and manufacturing. Yet, this aggregate prowess masks fragility: per capita GDP languishes at $2,718, a fraction of developed peers, underscoring uneven distribution.

Contrast this with Singapore in 1980. Singapore Airlines (SIA), the national flag carrier, faced a pilots' strike led by the Singapore Airline Pilots' Association (SIAPA). Demanding better pay amid soaring fuel costs, 1,300 pilots halted operations, stranding passengers and threatening the airline's nascent global ambitions. At stake was not just flights, but Singapore's reputation as a reliable hub.

Enter Lee Kuan Yew, the founding Prime Minister whose "iron in the soul" defined the nation. In a 65-minute meeting, Yew didn't negotiate—he dictated. "Get back to work, restore discipline, then argue your case," he thundered, threatening to ground SIA indefinitely, fire all strikers, and rebuild the airline from scratch with foreign talent. The pilots capitulated, operations resumed, and Yew's resolve became folklore. In a rally speech, he declared, "This is not a game of cards. This is your life and mine. I spent a whole lifetime building this. And as long as I'm in charge, nobody's going to knock it down."

This episode wasn't authoritarian whim; it was strategic pragmatism. Singapore, with no natural resources, bet on human capital and rule of law. Yew's People's Action Party (PAP) enforced meritocracy, breaking unions that could derail progress. Today, SIA thrives as a five-star airline, its monopoly tempered by fierce global competition.

Singapore's aviation sector, bolstered by Changi Airport—the world's best—handles 68 million passengers annually with minimal disruptions. In monopolies, this manifests acutely. Singapore's Competition and Consumer Commission fines violators swiftly; India's antitrust body, under-resourced, rarely challenges bigshots. The IndiGo exemption? A symptom of regulatory capture, where growth trumps accountability.

Singapore's success isn't genetic; it's engineered. Yew's authoritarian efficiency—curbed freedoms for collective gain—built institutions that outlast him. India, with its vibrant democracy, must adapt: bolster regulators, diversify sectors (aviation needs more players like a revived Air India), and enforce anti-monopoly laws sans political bias. The 2025 Ipsos survey shows Indians' economic worries easing (inflation down 12%), but climate and healthcare anxieties rise—areas where Singapore excels via foresight.

Yet, India's scale is its superpower: 1.4 billion innovators could eclipse Singapore's model if channelised. The IndiGo fiasco isn't defeat; it's a wake-up. As Pandhi's post implores, India needs leaders with "stomach" for tough calls—not surrender, but strategic confrontation. Emulate Yew's iron, temper it with Gandhian equity, and 2030's $7 trillion economy could uplift millions, not just a few elites.