Jagan Mohan Reddy's political revival: A critical analysis

07-02-2026 12:00:00 AM

In the ever-evolving landscape of Andhra Pradesh politics, YSR Congress Party (YSRCP) leader Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy has announced his return to active political engagement after a period of relative silence following his electoral defeat. Critics argue that Jagan's approach to politics has been inconsistent, marked by detachment from his party workers and the public once in power. During his tenure as Chief Minister, Jagan reportedly severed ties with grassroots supporters, focusing instead on a close-knit circle of advisors.

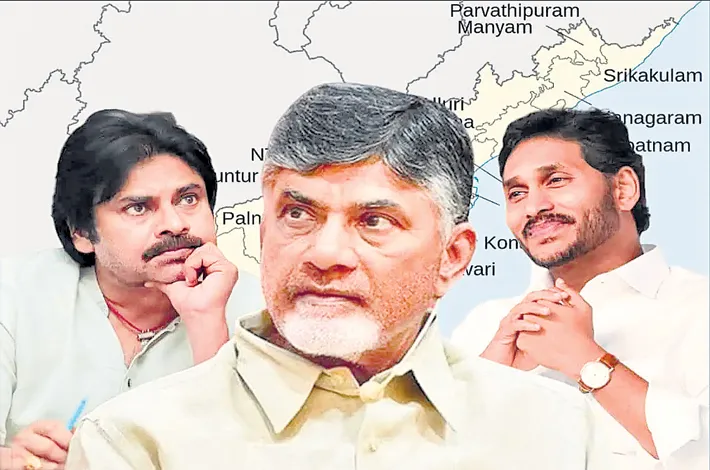

This isolation, observers note, began the day he assumed office, leading to a perception that he was more engaged in personal pursuits than public service. His recent press meet, where he declared intentions to undertake another padayatra (foot march) and reconnect with cadres, is seen as a desperate attempt to revive the party's fortunes amid dwindling activity in most districts. The discussion highlights a stark contrast in leadership styles between opposition and ruling periods. When out of power, leaders like Jagan and Telugu Desam Party (TDP) chief N. Chandrababu Naidu are vocal and accessible, promising grassroots involvement.

However, in power, they adopt a glamorous, celebrity-like persona, prioritizing media appearances over party interactions. Chandrababu, described as a democrat rather than a dictator, is unlikely to obstruct Jagan's padayatra, as doing so could generate sympathy for the YSRCP leader. Political analysts point out that such marches have historically built public sentiment in Andhra Pradesh, though success depends on broader circumstances rather than the act alone. Jagan's previous padayatra propelled him to victory, but his sister Y.S. Sharmila's similar effort yielded no results, underscoring that charisma and context matter more than the march itself.

A key critique revolves around the disconnect between leaders and their workers. In YSRCP, party cadres were allegedly neglected for five years, with Jagan viewing welfare schemes as transactional—distributing benefits in exchange for votes without personal engagement. This "give and take" mentality, critics say, eroded loyalty. Similarly, TDP workers feel sidelined now that the party is in power, with leaders like Chandrababu and his son Nara Lokesh living in an illusion that invoking Jagan as a "bogeyman" will secure future votes.

The conversation draws parallels with other states, noting that arresting opposition figures like Jagan or Telangana's K.T. Rama Rao often backfires by creating sympathy. Chandrababu's past arrest by Jagan is cited as a foolish move that could have been timed better to avoid electoral repercussions. The dialogue also delves into party ideologies and structures. Regional outfits like TDP and YSRCP lack strong principles, treating power as the ultimate goal and importing "inorganic" leaders for financial or electoral gains.

In contrast, national parties like BJP emphasize "organic" growth, prioritizing long-term cadres over outsiders, as seen in appointments like those of Madhav and Sathya Kumar. This approach, influenced by RSS, ensures loyalty but limits flexibility. The speakers lament that both TDP and YSRCP indulge in similar malpractices—land grabbing, mining scams, and cadre neglect—regardless of who is in power. Public disillusionment stems from unchanged systems, where local officials remain influenced by MLAs rather than district authorities.

Speculation surrounds figures like Vijaya Sai Reddy, a key YSRCP strategist rumored to defect to BJP with influential members. However, his lack of grassroots appeal—he is seen more as a manipulator than a leader—casts doubt on his independent viability. The conversation warns that Jagan's aggressive rhetoric, including threats of retribution ("showing stars" to adversaries), echoes similar promises from Lokesh and others, fostering a culture of vengeance in politics. While this motivates cadres short-term, it risks alienating the broader public, who ultimately vote based on emotions rather than arithmetic calculations of seats.

Looking ahead, Jagan's padayatra, planned in about 18 months, could intensify political activity but may lead to unrest if not controlled. The government's machinery, fearing Jagan's return, might hesitate to intervene, allowing rowdyism to prevail. This could portray the ruling alliance as weak, benefiting the public through heightened accountability. However, the speakers emphasize that true progress requires both sides to engage genuinely with workers and address systemic failures. As Andhra Pradesh braces for renewed political fervour, the key question remains whether leaders will learn from past illusions or perpetuate the cycle of detachment and opportunism.