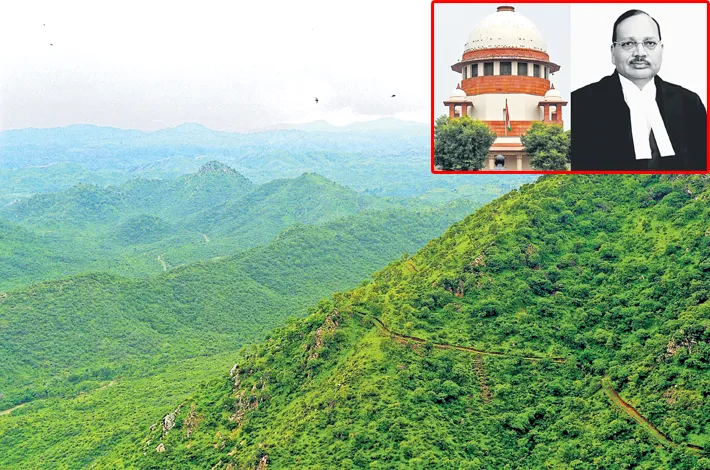

Supreme stays own verdict on Aravalli: What’s the way forward?

02-01-2026 12:00:00 AM

Original Supreme Court verdict:

Accepted government committee's recommendation defining "Aravalli Hills" as landforms with elevation of at least 100 metres above local relief, and "Aravalli Ranges" as clusters of such hills within 500 metres of each other.

What critics object to:

This criterion would exclude majority of the range — potentially over 90% in some estimates — stripping it of environmental protections and enabling ecologically hazardous mining activities.

What opposition says:

Accused the government of manipulating the definition to benefit mining interests, claiming it effectively imposes a "ban on the Aravalli itself" by excluding 90% of the hills.

New verdict:

- Directed formation of a new high-powered expert committee to conduct a thorough reassessment

- Previous verdict kept in suspension

Government’s response:

- Welcomed the Supreme Court's move. Reassured that the government remains fully committed to protecting and restoring the Aravalli range.

- Reaffirmed that the existing complete ban on new mining leases and renewals continues in entire Aravalli range

What environmentalists caution:

Express concern that a long wildlife corridor might be broken into smaller, isolated zones destroying ecosystem services unrelated to hill height— such as water security, biodiversity, and desertification control.

In a significant development hailed by environmentalists and sections of the public, the Supreme Court of India has put its November 20, 2025 judgment on the definition of the Aravalli Hills and Ranges in abeyance (suspended until further review). The decision, taken suo motu by a three-judge bench led by Chief Justice Surya Kant during the court's winter vacation, comes after widespread concerns that the earlier ruling could open the door to large-scale mining in the ecologically fragile, nearly 2-billion-year-old mountain system.

The original November 20 verdict, delivered by a bench headed by then-Chief Justice B.R. Gavai just days before his retirement, accepted a government committee's recommendation defining "Aravalli Hills" as landforms with an elevation of at least 100 metres above the local relief, and "Aravalli Ranges" as clusters of such hills within 500 metres of each other. Critics, including environmental activists, argued that this narrow criterion would exclude the majority of the range — potentially over 90% in some estimates — stripping it of environmental protections and enabling mining activities.

The Supreme Court, acknowledging "critical ambiguities" in the earlier definition and concerns about irreversible ecological damage, has now directed the formation of a new high-powered expert committee to conduct a thorough, scientific reassessment. The matter is listed for further hearing on January 21, 2026. In the interim, the November 20 recommendations and directions remain suspended to prevent any irreversible actions.

Union Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav welcomed the Supreme Court's move, stating that the government remains fully committed to protecting and restoring the Aravalli range. He reaffirmed that the existing complete ban on new mining leases and renewals continues, and assured that the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change would extend all necessary assistance to the process. A BJP spokesperson defended the Modi government’s overall environmental record and pointed out that the Union Environment Ministry had already declared on December 24, 2025 — before the Supreme Court’s latest order — that no new mining leases would be granted in the Aravalli region in Gujarat, Delhi, Haryana, and Rajasthan.

In contrast, Congress leaders, including former Rajasthan CM Ashok Gehlot and Jairam Ramesh, hailed the stay as a victory for public pressure and environmental sanity. They accused the Modi government of manipulating the definition to benefit mining interests, claiming it effectively imposes a "ban on the Aravalli itself" by excluding 90% of the hills. Gehlot stressed that the range is not anyone's property but a millennia-old protector of the region, warning that the BJP's control over the Centre and four states enables destruction. Ramesh and others described the original move as "dangerous and disastrous," an attack on water sovereignty, air quality, and North India's climate. Congress welcomed the court's intervention as "much needed," urging a scientific review that considers the full ecological sensitivity, impact on locals, and natives.

A veteran bureaucrat and environmental expert argued that even under the best estimates, no more than 5-10% of the range would qualify under the 100-metre rule, calling the shift a "well-planned move" to circumvent longstanding court-imposed restrictions and earlier government orders. He warned that the definition would shatter a long wildlife corridor into smaller, isolated zones, destroying ecosystem services unrelated to hill height or geological age — such as water security, biodiversity, and desertification control.

As 2025 ends, the Aravalli episode is being widely viewed as a landmark moment demonstrating the combined force of investigative journalism, public mobilization, and judicial openness in protecting India’s natural heritage. While political blame games continue, the core demand remains unchanged: a balanced, science-based, and precautionary approach to safeguard one of the world’s oldest mountain systems for future generations. Senior advocates and legal experts clarified that any mining license issued after November 20, 2025 would be void ab initio (invalid from the beginning) under the current abeyance order, and that state governments must now cancel such permissions to avoid contempt of court.

Few core questions asked were-Were dozens of mining leases granted in a 16-day window between the original judgment and the Centre’s “no new leases” announcement ; if so, will those licenses now be cancelled given the abeyance order and why were illegal mining violations and whistleblower intimidation not addressed earlier?