The Mist of Tawang

30-05-2025 12:00:00 AM

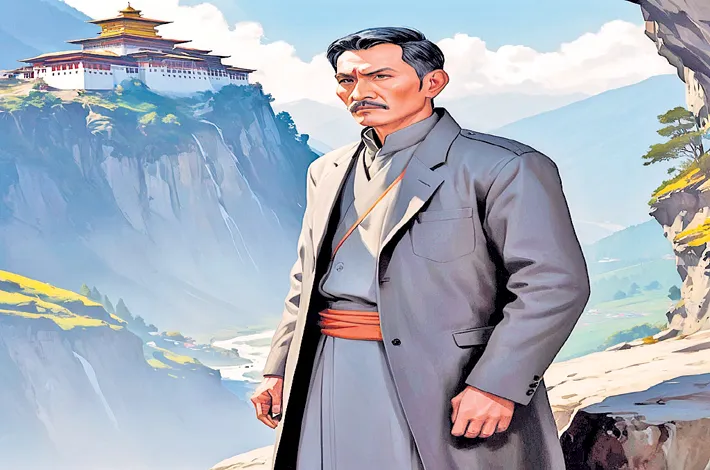

In the heart of Arunachal Pradesh, where the jagged peaks of the Eastern Himalayas pierced the clouds, Tawang lay cloaked in mist and mystery. Inspector Tenzin Dorjee, a wiry man with a weathered face and sharp eyes, stood at the edge of a cliff overlooking the Tawang Monastery.

The air was crisp, heavy with the scent of pine and the distant toll of prayer bells. Below, the town stirred uneasily under a pall of suspicion. A prominent local trader, Wangdu Lama, had been found dead in his sprawling mansion, a yak-bone dagger plunged into his chest.

Tenzin adjusted his woolen cap, his breath fogging in the chilly dawn. The call had come at midnight from Sub-Inspector Pema, a young officer stationed at the Tawang police outpost. “It’s bad, sir,” she’d said, her voice trembling. “Blood everywhere. Looks like murder.” Tenzin had seen his share of petty thefts and border skirmishes, but murder in Tawang was rare. The town was a close-knit tapestry of Monpa tribes, Buddhist monks, and transient traders. Everyone knew everyone, or so it seemed.

The crime scene was a grim tableau. Wangdu’s mansion, perched on a hill, was a blend of traditional Monpa woodwork and modern opulence. Inside, the trader’s body lay sprawled in his study, the dagger’s ornate handle glinting under a flickering bulb. Blood pooled on the intricately woven carpet, staining its vibrant reds and blues. Tenzin crouched beside the body, noting the precision of the wound. “No struggle,” he muttered. “Whoever did this was quick. Trusted, maybe.”

Pema, hovering nearby, handed him a plastic bag containing a crumpled note found in Wangdu’s pocket. Scrawled in crude Devanagari script were the words: “The debt is paid.” Tenzin’s brow furrowed. Wangdu was known for his ruthless business dealings—smuggling rare herbs and artifacts across the Indo-China border. Had he crossed the wrong person?

The investigation began with the household. Wangdu’s wife, Sonam, was inconsolable, her sobs echoing through the wooden corridors. “He had enemies,” she admitted between tears. “But who would do this?” The servants, a tight-lipped lot, offered little. The cook, an old Monpa woman named Dawa, mentioned a heated argument Wangdu had with a stranger two nights prior, but she hadn’t seen the man’s face.

Tenzin’s first lead came from the local market, a bustling maze of stalls selling yak butter, prayer flags, and smuggled Chinese electronics. A tea vendor, Rinchen, whispered about Wangdu’s ties to a shadowy figure known only as “The Yak.” Rumored to be a smuggler operating out of Bomdila, The Yak controlled the flow of contraband through Arunachal’s rugged terrain. Tenzin’s gut told him the note’s mention of a “debt” pointed to this elusive figure.

With Pema in tow, Tenzin drove his battered jeep down the winding roads to Bomdila, the mist clinging to the mountains like a shroud. The town was quieter than Tawang, its streets lined with prayer wheels and small monasteries. At a dimly lit bar, Tenzin met an informant, a former smuggler named Karma. Over steaming cups of butter tea, Karma confirmed The Yak’s existence. “He’s not just a smuggler,” Karma said, glancing nervously at the door. “He’s a ghost. No one’s seen his face, but he’s got eyes everywhere.”

Karma slipped Tenzin a name: Tashi, a local guide who’d been seen with Wangdu recently. Tracking Tashi down proved difficult. The guide was a nomad, moving between villages, but a tip led Tenzin to a remote yak herder’s camp near Sela Pass. The high-altitude air bit at Tenzin’s lungs as he and Pema trekked through snow-dusted trails. They found Tashi tending a fire, his face half-hidden by a fur-lined hood.

Tashi was cagey, denying any connection to Wangdu’s death. But when Tenzin pressed him about the note, Tashi’s eyes flickered with fear. “I only delivered a package,” he stammered. “Wangdu owed The Yak money. A lot. I don’t know more.” Under pressure, Tashi revealed a meeting spot—a derelict monastery near Dirang where The Yak’s men collected payments.

The monastery was a crumbling relic, its walls etched with faded thangkas. Tenzin and Pema arrived under cover of darkness, the wind howling through the valley. Inside, they found signs of recent activity: cigarette butts, a discarded satphone, and a ledger listing transactions in coded symbols. Tenzin’s heart raced as he deciphered names linked to Wangdu. One entry stood out: a debt of ten crores, marked “settled” in fresh ink.

A rustle outside snapped Tenzin to attention. He signaled Pema to take cover behind a prayer wheel. Two figures emerged from the shadows, their faces obscured by scarves. One carried a rifle, the other a familiar yak-bone dagger. Tenzin’s mind raced—had The Yak sent enforcers to clean up loose ends?

The confrontation was swift. Pema, quick on her feet, disarmed the rifleman with a well-placed kick, while Tenzin tackled the other, wrestling the dagger free. Under interrogation, the men revealed they were hired muscle, sent to retrieve the ledger. The Yak, they claimed, was no single person but a syndicate, and Wangdu’s death was a warning to others who defaulted on debts.

Back in Tawang, the ledger cracked the case wide open. It implicated a local official, Dorji, who’d been skimming profits from the smuggling ring. Confronted with the evidence, Dorji confessed. Wangdu had threatened to expose him unless he paid up. Desperate, Dorji had hired a hitman, staging the murder to look like a syndicate hit, complete with the cryptic note to throw off suspicion.

As Tenzin watched Dorji being led away in handcuffs, the mist began to lift over Tawang. The monastery bells tolled, a reminder of the fragile peace in these mountains. Pema, still shaken, asked, “Will The Yak come for us now?” Tenzin lit a cigarette, exhaling into the cold air. “Let them try,” he said, his eyes fixed on the horizon. In Arunachal, the mist hid many secrets, but Tenzin Dorjee was no stranger to chasing shadows.