Vision for a pure Gau Mahadhamam

14-10-2025 12:00:00 AM

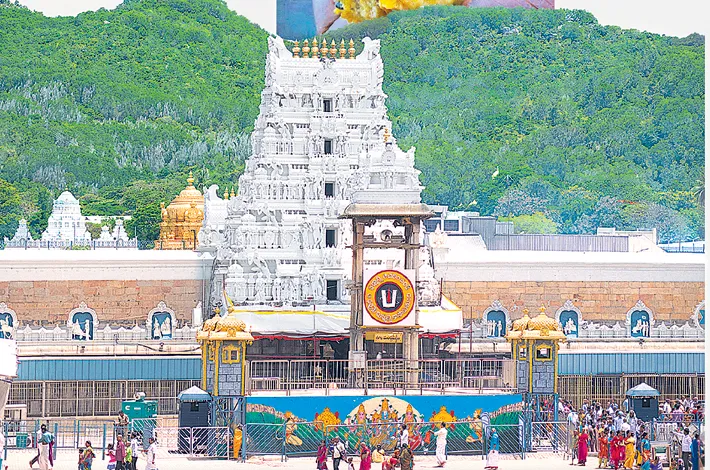

In the heart of Andhra Pradesh's Chittoor district, where the sacred Tirumala hills rise like a divine sentinel, the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams (TTD) stands as a beacon of devotion for millions of Hindus worldwide. Managing the world's richest temple, the Sri Venkateswara Swamy Temple, TTD oversees not just spiritual rituals but an ecosystem of faith, economy, and tradition. At its core lies the humble yet hallowed prasadam—the laddu, a fist-sized sweet ball infused with the essence of devotion, ghee, and purity. But in September 2024, this symbol of divine grace became a flashpoint for national outrage when allegations surfaced that the laddus were tainted with adulterated ghee containing animal fats like beef tallow, lard, and fish oil.

The controversy, erupting just months after a change in state government, exposed deep fissures in the supply chain of sacred offerings and ignited calls for radical reforms. Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N. Chandrababu Naidu decried the previous administration for compromising the "purity" of the temple's offerings, citing lab reports from Gujarat that detected foreign fats in samples supplied by Tamil Nadu-based A.R. Dairy Foods Pvt Ltd. The Supreme Court of India stepped in, ordering a CBI-monitored Special Investigation Team (SIT) probe to assuage the sentiments of "millions of devotees across the globe."

By February 2025, the SIT had arrested four individuals linked to the supply chain, revealing a web of proxy companies funneling substandard ghee despite blacklisting. This scandal wasn't merely about food safety; it struck at the soul of Hindu tradition, where ghee—clarified butter from cow's milk—symbolizes unadulterated sanctity. Panchagavya, the ancient Vedic mixture of cow milk, curd, ghee, dung, and urine, underscores the cow's revered status as "Gau Mata," the mother goddess sustaining life and rituals.

The Tirupati laddu, granted Geographical Indication (GI) status in 2009, traces its origins to 1715, evolving from the simpler "Manoharam" sweet into a global icon of piety. Each day, TTD's Laddu Potu kitchen—staffed by over 600 skilled "Pachakas" (cooks)—prepares up to 3.2 lakh laddus using 15,000 kg of cow ghee, alongside gram flour, sugar, and cardamom.

Distributed free or sold at nominal prices, these prasadam items generate revenue while embodying bhakti (devotion). But the 2024 scandal revealed vulnerabilities: reliance on external suppliers like A.R. Dairy, which secured a tender at Rs 320 per kg, led to corners cut for profit. Lab tests on July 8, 2024, samples showed contaminants exceeding vegetable oil limits, prompting TTD's immediate blacklisting of the firm.

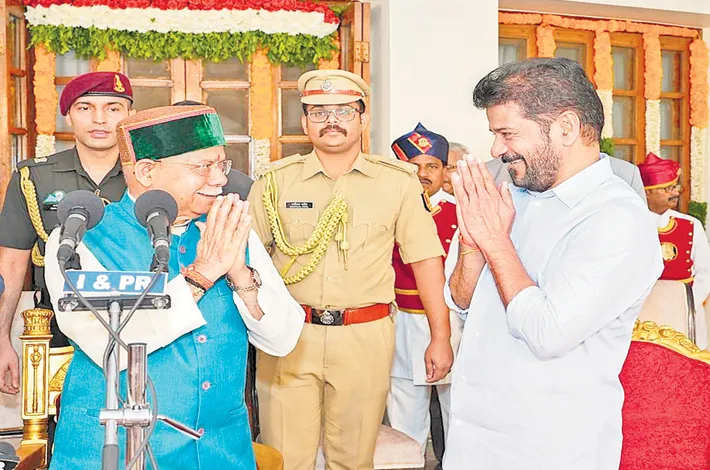

Adulteration wasn't just unhygienic; it was sacrilegious. As the dust settled, new proposals came forward. K. Shiva Kumar, Chairman of Yuga Tulasi Foundation , a Hyderabad based NGO and former member of the TTD Governing Council has submitted a comprehensive report to TTD officials advocating for the establishment of a "Gau Maha Dhamam" (TTD Mega Dairy) comprising one lakh indigenous cows. The proposal was presented to TTD Joint Executive Officer (JEO) Smt. Goutami, IAS, and Additional Executive Officer (EO) Sri Venkayya Choudhary.

The detailed report outlines the vision for a TTD-managed mega dairy aimed at promoting the conservation and utilization of indigenous cow breeds. Sri Shiva Kumar also presented the same report to Jagadguru Sri Shankar Vijayendra Saraswati Swamy, seeking blessings and support for the ambitious project. The initiative is seen as a significant step toward preserving India’s native cattle breeds while aligning with TTD’s objectives of promoting sustainable and traditional practices.

The Yuga Tulasi Foundation has emphasized the cultural and ecological importance of the project, urging TTD to take swift action to bring this vision to fruition.This self-sustaining dairy ecosystem would produce pure milk for ghee and prasadam items like laddus, vade, and payasam, directly addressing adulteration risks. By controlling the supply chain, TTD could ensure every drop of ghee aligns with Vedic purity, bypassing third-party vulnerabilities.

Historical precedents support this model: temples like the Jagannath Temple in Puri maintain in-house dairies for Mahaprasad, blending spirituality with self-reliance. TTD, with annual revenues exceeding ₹3,500 crore from donations and hundi collections, is uniquely positioned to execute this under the Andhra Pradesh Charitable and Hindu Religious Institutions Act, which mandates preserving sanctity.

Feasibility, however, hinges on scale and execution. Sourcing from 700 villages—spanning Tirupati's rural hinterland—implies a community-driven model, where farmers contribute unproductive cows in exchange for fodder subsidies or veterinary aid. This aligns with the National Livestock Mission's push for stray cattle management, amplified for sacred ends. India, home to 307 million cattle (per 2019 Livestock Census), reveres the cow as a living deity, yet grapples with 5.28 million strays—abandoned post-lactation due to economic pressures. TTD's initiative could transform this challenge into an opportunity, creating a blueprint for other temples.

Lessons from the world's largest cow sanctuaries

Gaushalas, ancient sanctuaries for aged, infertile, or rescued bovines, number over 7,000 in Uttar Pradesh alone, housing 16 lakh strays. Funded by donations, government grants, and temple trusts, they blend philanthropy with utility: biogas from dung, organic manure, and limited dairy. Pathmeda Godham in Rajasthan's Barmer district exemplifies mega-scale success, sheltering 85,000 cows across 1,200 acres. Established in 2001 by the Goyal family, it generates ₹50 crore annually from milk (yielding 1.5 lakh liters daily), ghee, and value-added products like soap and medicines. Veterinary care, solar-powered fencing, and community involvement keep mortality below 5%, far outperforming smaller shelters' 20-30% rates.

For TTD, these lessons are gold. Unlike secular gaushalas, TTD's would leverage spiritual capital: devotees' donations could fund infrastructure, while Vedic scholars ensure ethical breeding (no artificial insemination for "purity"). Sourcing from 700 villages aligns with AWBI guidelines, reducing strays that damage crops (Rs 2,000 crore annual losses in UP). Existing TTD facilities, like the Sapthagiri Gau Pradakshina Shala in Alipiri—hosting rituals like the daily Sri Srinivasa Divyanugraha Homam—provide a blueprint for expansion.

Challenges persist, demanding rigorous planning. A 2019 PMC study of 14 gaushalas found 92% of cows adequately hydrated but 40% lame from poor footing, and 25% with mastitis due to overcrowding. Funding gaps—₹5.8 billion spent nationally from 2014-2016—yield incomplete facilities, with Uttar Pradesh's 321 large shelters (capacity: 400 each) still overrun. Corruption scandals in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh highlight mismanagement, where crores vanish into ghost shelters. TTD must prioritize transparency, leveraging its robust governance to avoid such pitfalls.

Logistical blueprint: Sourcing a lakh cows

Housing 100,000 cows demands meticulous planning. At 200-300 sq ft per cow (per AWBI standards), the shala requires 20-30 million sq ft—roughly 1,500-2,000 acres—ideally on TTD-leased forest or barren land near Tirupati, minimizing urban sprawl. Phased construction could start with 20,000-cow modules, scaling via modular barns with ventilation to combat Andhra's heat (average 35°C summers). Sourcing from 700 villages (population ~5 lakh) involves GPS-mapped drives, offering incentives like free insemination for productive herds or biogas plants for dung. Indigenous breeds like Sahiwal or Gir predominate (48% of Indian cattle), thriving on local fodder but yielding modestly.

Health protocols are paramount. Employ 200 vets for routine checks, vaccinations, and AI-driven lameness detection. Colostrum feeding for calves (essential for immunity) and separation post-birth reduce mortality to less than 10%. Biosecurity—quarantine for newcomers, carcass composting—prevents outbreaks like foot-and-mouth disease. Waste management transforms liability into asset.

One lakh cows produce 500 tons of dung daily, convertible to 50,000 cubic meters of biogas (powering the shala) and 200 tons of organic fertilizer for TTD's 500-acre farm. Environmental audits ensure zero effluent, aligning with NGT norms. Community buy-in is key. Train 5,000 villagers as "Gau Rakshaks" for daily care, fostering employment in a region where 60% rely on agriculture. Partnerships with NDDB (National Dairy Development Board) could introduce silage-making, boosting fodder self-sufficiency.

Economic engine: From milk to mega-revenues

The dairy math is compelling. An average Indian cow yields 5-8 liters daily (vs. 30+ for Holsteins), so 100,000 cows produce 500,000-800,000 liters/day which is enough for TTD's 15,000 kg ghee (requiring ~150,000 liters milk) plus surplus. One liter milk yields 0.4-0.5 kg ghee, enabling 60,000-75,000 kg annually beyond needs, sold as "Sri Vari Ghee" at premium (₹800/kg vs. market ₹500). Prasadam diversification could use milk for paneer-based sweets, flavored payasam, or probiotic curd for pilgrims.

Pathmeda's model in Rajasthan projects Rs 200 crore revenue from dairy alone, offsetting Rs 150 crore annual costs (feed: ₹50/kg/month/cow; vet: ₹100/cow/month). TTD's ₹4,000 crore 2024 revenue cushions startup: Rs 500-1,000 crore for land/infra, recouped in 3-5 years via eco-tourism (Gau Puja circuits) and exports. ROI extends rurally. Villages gain from cow loans (₹20,000/animal under Mukhyamantri scheme), reducing abandonment. Nationally, it could inspire 100 such temple-gaushalas, curbing Rs 10,000 crore adulteration losses in dairy.

Cultural and spiritual resonance

Beyond economics, the Gau Maha Dhamam restores trust in Tirupati's sanctity. Devotees, scarred by the 2024 scandal, would see TTD's commitment to Vedic principles, reinforcing the temple's role as a global spiritual anchor. The project could also elevate indigenous breeds, whose populations have dwindled 20% since 2007 (per BAIF data), preserving biodiversity. Educational outreach—via TTD's YouTube channel or pilgrim workshops—could teach Gau Mata's significance, fostering a new generation of devotees rooted in tradition.

Challenges and pathways

Skeptics cite overcrowding risks, as in UP's incomplete shelters. TTD could cap occupancy at 80%, with satellite mini-shalas. Heat stress, prevalent in Andhra, demands shade nets and misting systems, as proven in Kerala dairies. Crowdfunding via TTD's app, targeting NRIs, could raise ₹100 crore annually. Regulatory nods from FSSAI and APPCB are feasible, given TTD's clout. Some farmers fear cow seizures. This requires trust-building through transparent cooperatives.

TTD's mega Gau Shala isn't just feasible—it's transformative. By 2030, it could house 100,000 cows, yield 2 lakh liters milk daily, and produce unadulterated ghee for laddus that devotees trust implicitly. Rooted in the 2024 scandal's ashes, this vision honors Gau Mata, empowers villages, and fortifies faith. As Tirumala's bells toll, a new era dawns: where purity flows from the udder to the altar, untainted by human greed. In reclaiming the cow's bounty, TTD doesn't just prevent adulteration—it resurrects sanctity, ensuring the Tirupati laddu remains a divine offering, pure in body and soul.