Gandhi’s Enduring Legacy Non-Violence and Hindu–Muslim Unity

30-01-2026 12:00:00 AM

Venkat Parsa | Hyderabad

Mahatma Gandhi was 78 when he was assassinated on January 30, 1948. Martyrs’ Day this year marks the 78th anniversary of his death. Gandhiji lived and died for the ideal of Hindu–Muslim unity. “Partition only over my dead body,” he declared. However, amid the horrific violence following Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s Direct Action Day call on August 16, 1946, leaders such as Sardar Patel and Jawaharlal Nehru viewed Partition as inevitable. Reluctantly, and much against his wishes, Gandhiji acquiesced to the tragic reality.

In today’s polarised times, Gandhiji’s steadfast commitment to Hindu–Muslim unity remains profoundly relevant. At a moment when violence is often glorified, he placed ahimsa (non-violence) and satyagraha at the centre of politics, arguing that a civilisation can advance only through moral means. For Gandhiji, the purity of means was as important as the nobility of ends; injustice could never produce a just outcome.

Satyagraha, he believed, could counter hatred with love. Interestingly, September 11 carries two contrasting meanings in history. While modern memory associates 9/11 with terror, another September 11— in 1906—marks Gandhiji’s launch of satyagraha in Johannesburg against the Transvaal Asiatic Registration Act, symbolising peaceful resistance.

A major milestone in the freedom struggle was Gandhiji’s support to the Khilafat Movement. At the 1919 AICC session in Amritsar, presided over by Motilal Nehru, the Congress resolved to back it. This drew Muslims into the national movement in large numbers and transformed the Congress into a mass organisation.

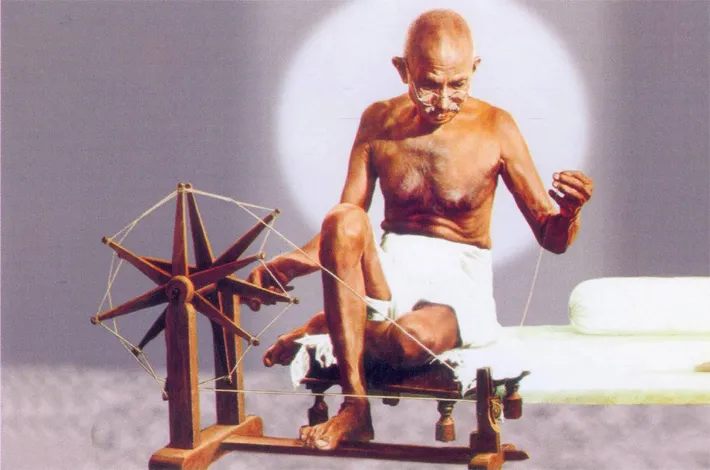

Gandhiji placed Hindu–Muslim unity at the core of his Constructive Programme, alongside the removal of untouchability and promotion of khadi and village industries—echoing Mughal emperor Akbar’s belief that unity formed the basis of Indian nationhood.

At the 1920 AICC session in Kolkata, Gandhiji moved the Non-Cooperation resolution, igniting nationwide participation. Yet after the Chauri Chaura violence in 1922, he suspended the movement, insisting that ahimsa was more important than independence. For him, non-violence had to guide thought, word and deed.

Gandhiji’s philosophy inspired global leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela and Lech Walesa. After Independence, Jawaharlal Nehru carried forward Gandhian ideals through India’s commitment to peace, opposition to nuclear weapons, and advocacy of disarmament—efforts later advanced by Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi.

In 2007, Sonia Gandhi revived Gandhian thought through an international conference and successfully pushed for the UN to designate October 2 as International Non-Violence Day, reaffirming the timeless relevance of Gandhiji’s ideals.