Irony of Bharat Rashtra Samithi

26-08-2025 12:00:00 AM

metro india news I hyderabad

The recent attempted protests by the Bharat Rashtra Samithi (BRS) student wing at Osmania University during Chief Minister A. Revanth Reddy’s visit on Monday, to inaugurate new hostels and a digital library, highlight a deep irony in Telangana’s political landscape.

The BRS, which led the Telangana statehood movement, now finds its student wing protesting against a Congress-led government, while the same party, under former Chief Minister K Chandrasekhar Rao (KCR), failed to address the entrenched police presence in universities during its decade-long rule. This incident underscores a broader historical phenomenon in India: the transformation of university campuses into virtual police camps, a practice that began in the 1970s with the rise of the Naxalite movement and persisted through movements like the Telangana agitation.

The Genesis of Police Camps in Indian Universities

The practice of establishing police camps in Indian universities emerged prominently in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a period marked by the Naxalite movement’s rapid spread. The Naxalite uprising, which began in 1967 in Naxalbari, West Bengal, was initially a peasant revolt but quickly gained traction among urban students and intellectuals, particularly in states like West Bengal, Bihar, and Andhra Pradesh. Inspired by Maoist ideology, the movement attracted young, educated individuals disillusioned with socio-economic inequalities and systemic injustices. Universities became hotbeds of revolutionary fervor, with students organizing protests, rallies, and even underground activities under slogans like “Amar bari, tomar bari, Naxalbari” (My home, your home, Naxalbari).

The Indian state, perceiving the Naxalite movement as a significant internal security threat, responded with heavy-handed measures. By the early 1970s, police repression intensified, with Operation Steeplechase (1971) marking a coordinated military and police effort to crush the insurgency. As universities in West Bengal (e.g., Jadavpur and Presidency), Bihar (e.g., Patna University), and Andhra Pradesh (e.g., Osmania University) became centers of Naxalite recruitment, the government began deploying police forces directly onto campuses. This breached a long-standing post-independence norm that barred police from entering educational institutions without prior permission from university authorities. The justification was clear: campuses were no longer just centers of learning but potential breeding grounds for revolutionary violence.

This period saw the establishment of temporary police camps in universities, which, in some cases, evolved into permanent police outposts. In Andhra Pradesh, the creation of the Greyhounds, a special anti-Naxalite task force in 1985, further institutionalized police presence in response to Naxalite activities in regions like Telangana and Srikakulam. Universities, particularly Osmania University, became focal points for surveillance and control, as students were suspected of collaborating with Maoist groups.

The Telangana Movement and Police Camps in Universities

The Telangana movement, which gained momentum in the late 1960s and peaked again in the 2000s, further entrenched police presence in Telangana’s universities. The 1969 Telangana agitation, sparked by discontent over the violation of the Gentlemen’s Agreement (1956) and economic disparities between Telangana and Andhra regions, saw Osmania University students at the forefront. The agitation turned violent, with police firing on protesters, resulting in the deaths of approximately 360 students and activists. The state’s response included increased police deployment on campuses, with Osmania University becoming a focal point of repression.

By the 2000s, as the Telangana movement was reignited under KCR’s leadership through the Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS, later BRS), universities like Osmania and the University of Hyderabad became epicenters of agitation. Students organized jail-bharo campaigns, strikes, and protests, often clashing with police. The Andhra Pradesh government, then led by the Congress, turned campuses into virtual police camps, with iron fencing, pre-emptive arrests, and heavy security to curb protests. This period saw Osmania University likened to a “war zone,” with students facing lathi charges and detentions.

BRS’s Inaction Post-2014

When Telangana was formed on June 2, 2014, with KCR as its first Chief Minister, there was an expectation that the BRS government would dismantle the repressive police structures in universities, given its roots in the student-driven Telangana movement. However, over its nearly decade-long rule, the BRS did little to lift these restrictions. Osmania University remained under tight police surveillance, with students facing continued restrictions on protests and gatherings. This inaction fueled resentment among students, who felt betrayed by a government they had helped bring to power. The discontent was so palpable that during the 2017 Osmania University centenary celebrations, attended by then-President Pranab Mukherjee, KCR reportedly refrained from speaking, fearing student protests.

This failure to address police repression reflects a broader contradiction in the BRS’s governance. While KCR championed Telangana’s cultural and economic revival, his administration’s reluctance to liberalize campus environments suggests a prioritization of control over democratic freedoms. Critics argue that this was driven by a fear of student activism, which had historically challenged state authority, whether during the Naxalite movement or the Telangana agitation.

The Current Protests and Political Irony

The protests by the BRS student wing during CM Revanth Reddy’s visit to Osmania University on Monday, add a layer of irony to this narrative. The BRS, which once relied on student activism to achieve Telangana statehood, now finds its student wing protesting against a Congress government led by Revanth Reddy.

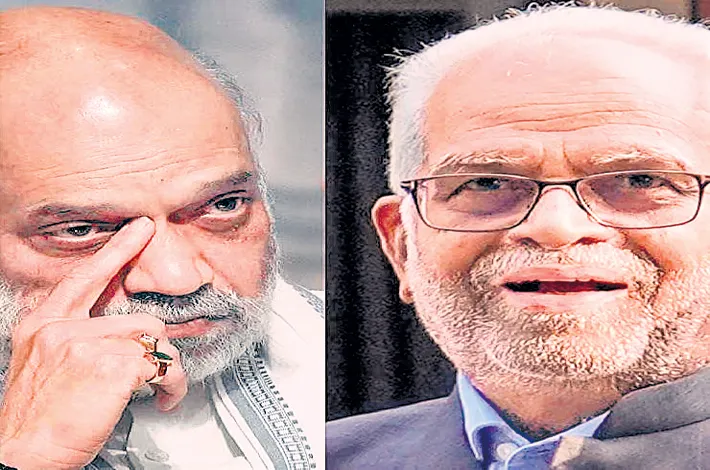

Reports indicate that BRS student leader G. Srinivas Yadav and others were placed under house arrest to prevent protests, with police erecting iron fencing on campus—tactics reminiscent of the united Andhra Pradesh era. BRS leader T. Harish Rao condemned these actions as “undemocratic” and “barbaric,” highlighting the party’s outrage at the suppression of student voices.

Yet, this stance is ironic given the BRS’s own failure to reform campus policing during its tenure. The protests reflect not only dissatisfaction with the current Congress government’s policies but also a broader frustration with the cyclical nature of political repression in Telangana’s universities. Students, once the backbone of the Telangana movement, continue to face restrictions regardless of the ruling party, raising questions about the state’s commitment to fostering free academic environments.