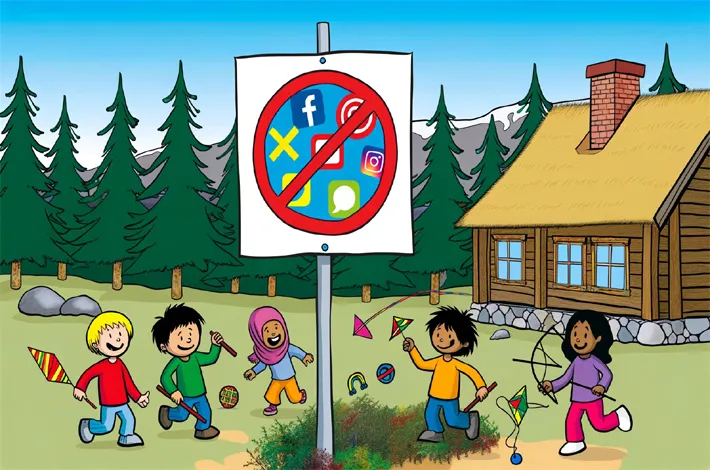

Will social media ban stop children from screens

31-01-2026 12:00:00 AM

Why did Australia ban social media for those below 16 years?

■ Protecting against harmful content

■ Reducing cyberbullying and grooming risks

■ Countering addictive design features

■ Safeguarding mental health overall

The debate over whether children under 16 should be legally barred from social media has intensified globally, with Australia leading the way as the first country to enforce a blanket ban on major platforms for minors in that age group. Implemented in December 2025, the Australian law prohibits under-16s from creating or maintaining accounts on services like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, X, YouTube, Snapchat, and others, with hefty fines—up to millions of Australian dollars—imposed on non-compliant tech companies.

Early reports indicate that hundreds of thousands to millions of accounts have been blocked or deactivated shortly after enforcement began, though concerns persist about teenagers using VPNs and other workarounds to bypass restrictions. France has followed closely, with its National Assembly recently approving legislation to ban social media access for those under 15, a move championed by President Emmanuel Macron as a step to curb excessive screen time, online bullying, and mental health risks. The proposal, which could take effect as early as September 2026, targets similar platforms and reflects growing international alarm over social media's addictive design features and exposure to harmful content.

Closer to home in India, the conversation is gaining traction at the state level. Goa and Andhra Pradesh are actively studying Australia's model, with officials in both states indicating they are exploring the feasibility of similar restrictions for children under 16. In Goa, the infotech minister has expressed intent to implement such a ban "if possible," while Andhra Pradesh authorities are preparing groundwork amid rising concerns about online addiction and abuse in a country with over a billion internet users. These discussions remain in early stages, with no national-level policy yet in sight, but they highlight mounting worries about children's vulnerability.

Medical and psychological evidence has fuelled the push for restrictions. Global studies, including the US Surgeon General's 2024 advisory, link more than three hours of daily social media use among adolescents to nearly double the risk of anxiety and depression. Experts also cite connections to poor sleep, body image issues (particularly among girls), cyberbullying, grooming, online abuse, and broader lifestyle problems emerging before age 30. A Child psychiatrist strongly endorsed a hard age cutoff, arguing that platforms prioritize business over safety.

He pointed to rising cases of depression, suicide ideation, gadget addiction, sleep deprivation from blue light exposure, and even sexual abuse linked to prolonged use. He described social media as more compelling than parents, friends, or teachers, and has urged Indian leaders, including the Prime Minister and IT Minister, to adopt Australia's approach. He emphasized that alternatives like WhatsApp exist for communication, and physical play, family interaction, and sleep should replace screen time to combat isolation and foster healthier brain development.

Critics, however, argue that blanket bans represent a blunt, potentially ineffective tool. CEO of a youth based online platform contended that social media is integral to young people's identity formation, self-expression, agency, and access to supportive communities—especially in India, where many youth discover belonging online. A total ban, she warned, could exacerbate social isolation, drive teens to unregulated "darker corners" of the internet via VPNs or new apps, and infantilize them rather than address root societal issues like inadequate listening to young voices. She advocated for holding platforms accountable through "safe by design" features, age-specific regulations (e.g., algorithm adjustments or content filters for teens), verifiable parental consent under frameworks like India's DPDP Act, and digital literacy programs instead of outright prohibition.

Founder of a school of groups highlighted practical failures in current safeguards. He noted widespread privacy violations—even by schools posting students' full names and details online—and parents unwittingly exposing children to permanent digital footprints. He questioned whether platforms build genuine agency, describing social media interactions as passive (likes/dislikes) rather than deep thinking or discernment. He favoured delaying access until children are ready, prioritizing emotional literacy, discipline, values, and real-world growth over forced online engagement.

A writer and journalist cautioned against repeating historical "moral panics" over technologies like television or video games. He advocated regulating systems and platforms—not users—citing China's time-limited, content-controlled version of TikTok for under-14s as a better model with guardrails. Bans, he argued, risk pushing users to unregulated spaces, undermine youth activism (e.g., platforms amplifying marginalized voices in events like the Iran protests), and deprive future citizens of information sources essential for democracy and discernment.

Proponents of bans see them as a necessary first step against an "epidemic" of addiction until better regulations emerge, while opponents favour nuanced, enforceable rules that preserve benefits like expression and community without snatching agency. As states like Goa and Andhra Pradesh consider pilots with review clauses, the issue strikes at the core of parenting, education, platform responsibility, and generational well-being—with no simple resolution in sight. The consequences for India's digitally native youth remain profound and hotly contested.