Gavai pushes creamy layer for SC/ST, ignites nationwide debate

18-11-2025 12:00:00 AM

■ CJI Gavai proposes extending creamy layer to SC/ST to target the truly disadvantaged.

■ Critics warn it could hollow out reservation benefits and divide communities.

■ Only a tiny fraction of SC/ST families are wealthy or hold Group A jobs.

■ Political leaders fear creamy layer could be weaponized to dismantle reservations.

■ Legal challenge expected in Supreme Court; debate pits equality versus intra-group fairness.

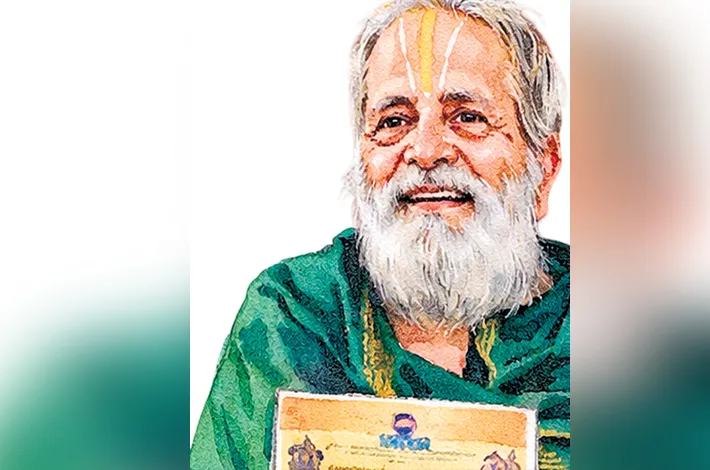

The debate over India’s reservation policies has once again reached the courtroom and political forefront, this time from the mouth of the retiring Chief Justice of India, B.R. Gavai. Speaking in Amaravati on November 16, 2025, at a program marking “India and the Living Constitution at 75 Years,” CJI Gavai reignited the long-standing controversy over the “creamy layer” in reservations, advocating its extension to Scheduled Castes and potentially Scheduled Tribes. His remarks have stirred fierce discussion: should the benefits of affirmative action be limited strictly to the truly disadvantaged within historically marginalized communities, or does this signal the beginning of a systematic erosion of quotas?

Reflecting on his judicial tenure and personal journey from a humble background in Amravati, Maharashtra, Gavai reaffirmed his long-held position on reservation policies. He explicitly endorsed applying the “creamy layer” concept—already used for Other Backward Classes since the 1992 Indra Sawhney judgment—to SCs and potentially STs. He said, “I also went further and took a view that the concept of creamy layer, as has been found in the judgment of Indra Sawhney, which is applicable to the Other Backward Classes, should also be made applicable to Scheduled Castes. Though my judgment has been widely criticized on that issue, I still hold that judges are not supposed to normally justify their judgments, and I still have about a week to go [before retirement].”

Gavai emphasized that reservation benefits should reach those who are economically and socially disadvantaged. Drawing a stark comparison, he said, “The children of an IAS officer cannot be equated with the offspring of a poor agricultural labourer.” He urged states to devise mechanisms to identify the creamy layer among SCs and STs and exclude them from quota benefits, arguing this approach aligns with the Constitution’s organic nature, as envisaged by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar under Article 368.

The “creamy layer” principle originated in the 1992 Supreme Court judgment in Indra Sawhney v. Union of India, arising from nationwide protests after the V.P. Singh government’s 1990 decision to implement the Mandal Commission report recommending 27 percent OBC reservation in central jobs. The nine-judge Supreme Court, in a 6:3 majority, upheld the quota but excluded the “creamy layer”—OBCs who had already achieved economic or professional advancement—from the benefits. Income, occupation, and social status were the yardsticks. Over decades, the Department of Personnel and Training revised the income threshold from Rs 1 lakh in 1993 to Rs 8 lakh in 2017. Judicial clarifications extended this principle to education through Ashoka Kumar Thakur in 2008 and even to children of constitutional office holders in 2015.

For over three decades, the creamy layer applied exclusively to OBCs. SCs and STs were exempt, given historical disadvantages and systemic marginalization. Even the landmark M. Nagaraj judgment in 2006 upheld SC/ST promotions without imposing creamy layer restrictions. The Union government has consistently opposed its extension to SC/STs, as seen in the 2018 Jarnail Singh ruling and the 103rd Constitutional Amendment, which restored SC/ST promotion benefits without any creamy layer restrictions.

Scholars and policymakers have suggested nuanced approaches to address intra-group inequality without dismantling existing reservations. The graduation principle proposes excluding only third-generation beneficiaries of high constitutional posts or families with sustained incomes above Rs 50 lakh. The deprivation index suggests combining rural residence, landlessness, caste-based labor history, and type of schooling instead of relying solely on income. The one-generation benefit model limits reservation benefits to one generation in education and employment, allowing children of affluent SC/ST families to compete in the general category while retaining protections under the SC/ST Atrocities Act.

Justice Gavai’s Amaravati remarks echoed his 417-page 2024 concurring opinion in the sub-classification case, citing data showing that only 1.13 percent of SC families are in Group A services yet disproportionately benefit from quotas. No state has formally implemented creamy layer rules for SC/STs, though Punjab sub-classified SCs post-2024, stopping short of income-based exclusions.

Tamil Nadu’s 69 percent quota remains untouched. Legal experts predict the issue may soon return to a nine-judge Supreme Court bench. Senior advocate Sanjay Hegde said, “Gavai’s opinion is persuasive but not binding. The court must reconcile Article 14 with Article 15(4) on intra-group equity.”

However, the creamy layer proposal for SC/STs has sparked alarm among political leaders and activists, who warn that it could become a tool to gradually dismantle reservations altogether. Mayawati, in August 2024, cautioned that “first they will impose creamy layer, then raise the income limit every year, and within a decade reservations will be empty.

” Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan added in 2024, “The day a Dalit child of a Class I officer loses reservation, the Brahminical state will celebrate the end of affirmative action.” Jignesh Mevani, in a 2025 interview, framed it as revenge by the upper-caste bureaucracy: “Every time a Dalit becomes an IAS officer, it is treated as a national calamity. Creamy layer is their revenge.”

These concerns are not new. Justice K. Ramaswamy’s dissent in 1992 warned that applying the creamy layer logic to SC/ST would amount to “rewriting the Constitution by judicial fiat.” Even the Indra Sawhney majority recognized the distinction between OBCs and SC/STs, observing that “while the backward classes can be divided into backward and more backward, the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes form one single class which cannot be subdivided.”

Data shows that the “cream” among SC/STs is microscopic. Government figures reveal that only 4.7 percent of SC households and 6.1 percent of ST households have a regular salaried job in the formal sector, according to the NSSO 78th Round (2021–22). Only 1.13 percent of SC families have a member in Group A central services, a figure cited by Justice Gavai himself in 2024. Less than 0.5 percent of SC/ST students reach elite institutions such as IITs and IIMs, even with reservation benefits. Prof. Sukhadeo Thorat, former UGC chairman, explains, “The cream is so thin that you need a microscope to see it. Excluding it will not free up seats; it will only satisfy upper-caste envy.”

The creamy layer debate goes beyond economics; it challenges the very purpose of India’s affirmative action. While CJI Gavai frames reservations as a tool for uplifting the truly disadvantaged, critics warn it could be a Trojan horse to erode SC/ST benefits, creating social divisions and legal disputes. As India marks 75 years of its Constitution, the discussion highlights the tension between intra-group fairness and protecting historically marginalized communities. With the affluent SC/ST segment being minuscule, questions arise over the necessity of reform. The outcome will influence reservation policy and the broader social and political fabric of the nation.