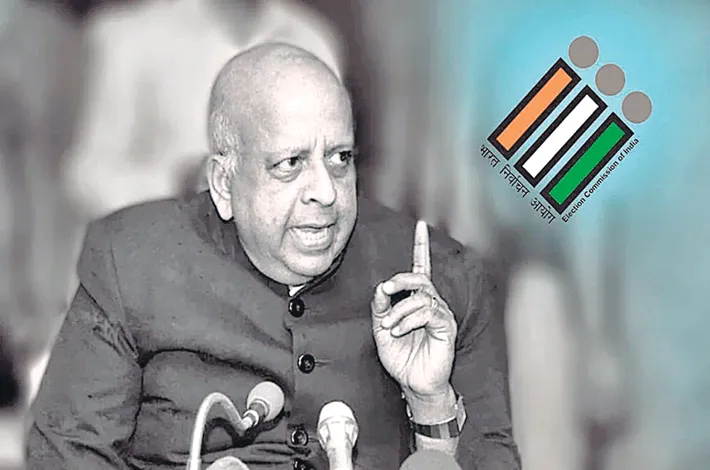

The Legend of T N Seshan

11-08-2025 12:00:00 AM

Once upon a time, in the bureaucratic steel frame of the country, a man named T.N. Seshan was nudged toward a job so obscure it made a librarian’s assistant look glamorous: Chief Election Commissioner (CEC). Seshan, a devout follower of the revered Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham’s HH Jagdguru Paramacharya Sri Chandrasekhara Saraswathi sauntered up to the “Walking God” and said, “I don’t want this job. Nobody even knows what a CEC does!” And he wasn’t wrong. The only folks who knew the CEC’s name were UPSC aspirants cramming for their current affairs quizzes, muttering “Perisastry who?” under their breath.

But the Paramacharya, with a twinkle in his eye and wisdom saw something Seshan didn’t. “Take the job, my boy,” he said, “You’ll make history, and your name will shine brighter than any politician ‘in the country. And, holy prophecy is right! T.N. Seshan didn’t just take the job; he grabbed it by the horns, turned it upside down, and made it sing “Jana Gana Mana” in perfect pitch.

Seshan didn’t invent the wheel or discover fire. No, he just dusted off the Election Commission’s rulebook, which was gathering cobwebs in some forgotten Delhi office, and enforced it with the zeal of a kid chasing an ice-cream truck. Political parties? Shaking in their boots. Candidates? Sweating like they’d been caught sneaking extra laddoos. Seshan’s mantra was simple: follow the law to the letter, or I’ll make you wish you were stuck in a never-ending Delhi traffic jam.

Take wall defacement, for example. Back in the day, political goons treated private walls like their personal graffiti canvases, scribbling slogans without so much as a “May I?” Seshan rolled in like a sheriff in a Bollywood Western, declaring, “Not on my watch!” Suddenly, campaign managers were double-checking property deeds before even thinking about a paintbrush.

Election expenditure? Oh, honey, Seshan had candidates counting every paisa, ensuring their spending stayed within limits tighter than a miser’s wallet. Ruling party bigwigs tried to pull rank, but Seshan wasn’t having it. When a Union Cabinet minister slipped him a sneaky “Demi-official” letter with “suggestions,” Seshan reportedly snapped, “I report to the President, not your Cabinet group!”

Even the media wasn’t spared Seshan’s headmasterly wrath. His press conferences were less “Q&A” and more “Listen up, kids!” He’d scold reporters for asking half-baked questions, urging them to “do their homework” before daring to quiz the mighty CEC. “I’m from Palghat,” he’d quip, “home of cooks and crooks!” Cue nervous laughter from the press corps, who weren’t sure if they were being roasted or recruited.

Seshan’s legacy? A bar so high it’s practically in orbit. He turned the CEC from a bureaucratic footnote into a household name, etched in gold in India’s democratic saga. Even today, when elections get murkier than a monsoon puddle, folks whisper, “We need another Seshan!” And who can blame them? In a world of political shenanigans, Seshan was the no-nonsense uncle who made everyone sit up straight and behave. So here’s to T.N. Seshan, the man who made democracy dance to his tune – and probably chuckled while doing it.

What Would Seshan Have Done today?

“I eat politicians for breakfast,” said T. N. Seshan in the 1990s — a line that came to define his fearless and assertive tenure as Chief Election Commissioner. The long-dormant Model Code of Conduct was revived under his watch, and ‘Sen Seshan,’ as the media fondly called him, brought the Election Commission of India to the forefront of the nation’s political discourse.

So how would Seshan have responded to today’s allegations — like Rahul Gandhi’s claims of voter list manipulation?

This was the man who identified 150 different electoral malpractices, who refused to buckle under pressure, and who publicly reprimanded seasoned politicians such as Sitaram Kesari and Kalpnath Rai for influencing voters during the 1994 Karnataka elections. In today’s climate, he would have launched a full-scale investigation — not waited for a signed affidavit. He would have gone all guns blazing.

Seshan would have insisted on audit trails and independent verification mechanisms for all changes to the electoral rolls. He would have mandated soft copies of voter lists, not just selective video footage. He would have enforced strict timelines for grievance redressal and held officials accountable — not deferred action.

He always maintained that the Election Commission had sufficient constitutional power — what was needed was the will to exercise it. He never waited for political approval or legislative amendments. He interpreted the EC’s mandate expansively, and he acted decisively.

The Big Difference Today

In Seshan’s time, they feared and respected the Election Commission. The Model Code of Conduct wasn’t just symbolic — it was central to any election discourse.

Today, the manipulation of electoral rules, deletion and addition of voters at will, and partisan interference in the voter list have become normalized. The public’s trust in the Election Commission is eroding. The selective enforcement of the Code of Conduct, unpunished inflammatory rhetoric, and an opaque functioning style have become major concerns.

The steady decline in the Commission’s assertiveness and its visible struggle to rein in malpractice would have deeply saddened him. Former Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Jayalalithaa once called him an “embodiment of arrogance.” Perhaps that’s exactly the kind of arrogance India needs today — principled, unrelenting, and grounded in constitutional authority.