Sahebnagar Kalan Case: A landmark win for Telangana Forest Dept

07-01-2026 12:00:00 AM

The Supreme Court judgment on the Sahebnagar Reserve Forest is more than just a legal victory. It sends a powerful message that a fast-growing state like Telangana can protect nature while managing urban growth responsibly. The case proves that development and environmental protection do not have to clash if the government acts firmly and follows the rule of law.

Sahebnagar Reserve Forest, part of the larger Gurramguda Reserve Forest, is located on the eastern side of Hyderabad in Rangareddy district. It lies near residential hubs like Vanasthalipuram, Gurramguda, and Sahebnagar Kalan along the Hyderabad–Nagarjuna Sagar Road. Spread across 465 acres, the forest acts as a green shield, reducing pollution, controlling heat, and supporting native plants and wildlife.

Legally, the forest has a clear history. It was notified as a reserve forest in 1971, with formal steps completed in 1972. Revenue and survey records consistently showed this as government forest land, and at the time of reservation, there were no valid private ownership claims. However, as Hyderabad expanded and land prices rose, old and questionable claims surfaced, especially over 102 acres allegedly inherited from the Salarjung estate. Such disputes are common in Indian cities, where historical confusion is used to challenge public land.

What sets the Sahebnagar case apart is the determination of the Telangana Forest Department. Officers across governments treated it as a matter of public interest rather than a routine legal file. Their sustained efforts led to the Supreme Court confirming that the disputed land is part of the Gurramguda Reserve Forest and belongs to the State. Leadership within the department played a crucial role. PCCF Dr. Suvarna ensured the long-pending case reached a final conclusion, acknowledging contributions from former PCCF Sri Muralidhar and retired CCF Sri Buchi Rami Reddy. This highlights a key truth in governance: institutions succeed when continuity and memory are respected. Environmental protection is a long-term effort built over generations of committed officers.

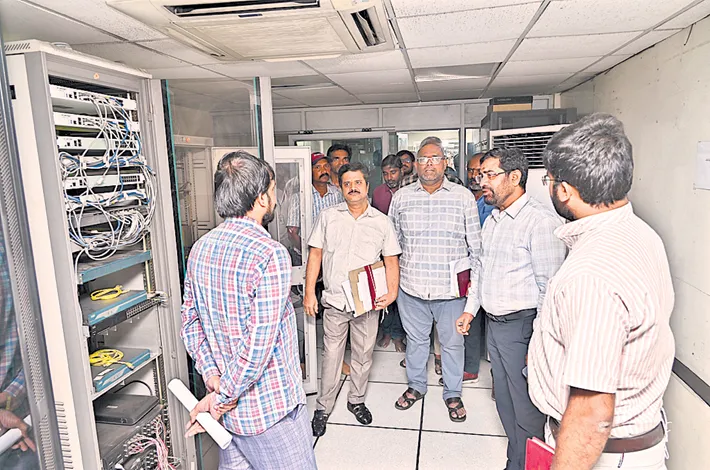

At media interactions, officers shared their struggles. Charminar Zone CCF Priyanka Varghese spoke about the legal hurdles and coordination with Delhi advocates, including Karanam Sravan Kumar. Senior IAS officer Yogitha Rana helped provide rare archival records, which proved decisive in court. PCCF Dr. Suvarna also highlighted the challenges women officers face while serving, sending a strong message to young public servants.

Political support was also crucial. Consistent backing from Chief Minister A. Revanth Reddy and Forest Minister Konda Surekha ensured that the department could pursue the case without compromise. Environmental governance cannot succeed if departments are left isolated.

The judgment also carries urban planning lessons. Hyderabad is rapidly growing, and green spaces are shrinking. Plans to fence and develop Sahebnagar as an urban forest park, similar to Arogya Sanjeevani Vanam, reflect a balanced approach—protecting nature while allowing controlled public access. Urban forests are essential for public health and climate resilience, not mere luxuries.

The felicitation of field officers, retired officials, and frontline staff at KBR National Park reinforced this message. One notable moment was the appreciation of 95-year-old retired CCF K. Buchi Rami Reddy, whose ability to read old Urdu documents exposed fabricated claims. State Archives verification confirmed these documents were fake, as official communication then was in Persian—a crucial factor in court.

The Sahebnagar verdict is a lasting example: forest land is not real estate for negotiation. Law, when pursued patiently and honestly, protects public assets. Sustainable urban development is possible only when forests are treated as assets for future generations. Telangana has shown that growth and green protection can coexist when intent is clear and commitment is real.