Unlocking India's agricultural growth-from welfare to reform

01-02-2026 12:00:00 AM

This issue is starkly illustrated in India's oilseed economy, especially mustard. Mustard cultivation spans about 9 to 10 million hectares and is central to reducing reliance on imported edible oils. In recent years, acreage expanded rapidly due to rising MSP and strong policy emphasis

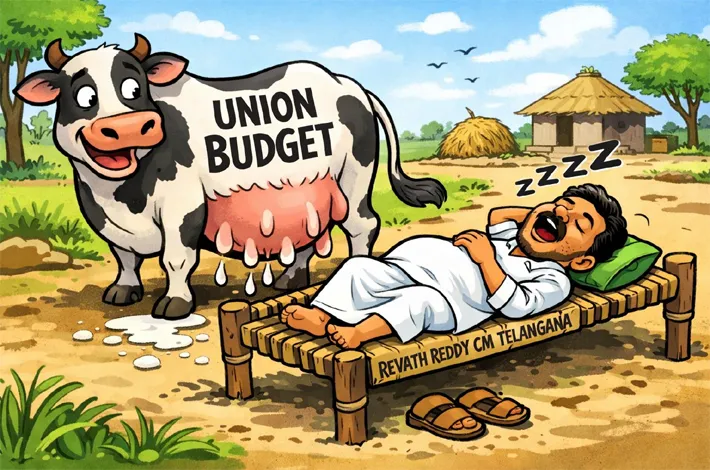

With the Union Budget on the horizon, agriculture is once again in the spotlight as a sector demanding protection, support, subsidies, and safeguards. This instinct is understandable—agriculture feeds India, employs nearly half of its workforce, and plays a pivotal role in controlling food inflation. However, viewing agriculture solely as a welfare obligation or an inflation management tool overlooks its immense potential. Agriculture is not merely a sector for government oversight; it represents one of India's most underutilized avenues for growth and, crucially, the most cost-effective reform option available to the state.

The signs of missed opportunities are evident on India's farms. Discussions about the sector's underperformance often cite familiar issues: small land holdings, climate stress, and overdependence on limited land. While these factors are significant, they fail to explain why productivity growth has stagnated even in well-irrigated regions with market access and policy focus. The root problem is simpler yet more challenging—agricultural incentives have remained static. When incentives cease to evolve, growth doesn't halt abruptly; it erodes gradually until biological factors reveal the damage.

This issue is starkly illustrated in India's oilseed economy, especially mustard. Mustard cultivation spans about 9 to 10 million hectares and is central to reducing reliance on imported edible oils. In recent years, acreage expanded rapidly due to rising minimum support prices (MSP) and strong policy emphasis on oilseed self-reliance. Farmers responded logically by planting more mustard, often repeatedly. However, this growth occurred without corresponding enhancements in procurement reliability, incentives for crop rotation, or adequate agronomic support. As a result, farmers intensified production in ways the system rewarded, leading to clear patterns in the data. Mustard acreage was stable for years before surging by over 20% in a single year. Yet, productivity—yields per hectare—remained flat despite the massive land increase. This reflects "area growth" rather than improved efficiency, signaling a problem rather than progress.

Farmers are often labeled risk-averse, but they are rationally navigating the risks the policy framework imposes. Price risks are buffered for select crops, while biological, climate, and market risks fall largely on individuals. This makes diversification appealing in rhetoric but fragile economically. Transitioning from cereals to oilseeds, pulses, or high-value crops exposes farmers to price swings, procurement inconsistencies, and policy U-turns. Under these conditions, sticking to familiar or newly promoted crops feels safest. The fallout extends beyond farms: monoculture regions face declining returns, ecological strain, and escalating fiscal burdens for the state.

India's most vibrant agricultural growth isn't in traditional cereals but in sectors like dairy, poultry, fisheries, shrimp aquaculture, and high-value horticulture. These use minimal land yet contribute a rising share of value added. Their success isn't driven by heavy subsidies but by clearer markets, robust private involvement, and minimal policy meddling. These areas enable farmers to escape low-productivity cycles, thriving because the system incentivizes growth rather than perpetual bailouts.

So, what should the Union Budget prioritize? As per economists as well as agriculture experts, the focus shouldn't be on increasing agriculture spending but on rewarding beneficial behaviors. First, ensure predictability: farmers need assurance against abrupt policy reversals during price spikes, through rule-based trade, transparent procurement, and defined support periods. Second, frame diversification as risk management, not just advice—supporting crop rotation, mixed farming, oilseeds, and protein crops with protections against biological and market risks, via extension services, early warnings, and agroeconomic research. This is essential growth infrastructure, not optional expenditure.

Third, redirect priorities from surplus management to enabling transitions. Funds wasted on storing excess grain or mitigating preventable shocks could instead bolster productivity and resilience. Agriculture stands as India's cheapest growth reform—it demands no new land, no revolutionary tech, and no vast fiscal outlays. It simply requires evolving incentives and faith in farmers' responses. The warning signs are already apparent in the fields; whether the Budget interprets them as a crisis or an opportunity will shape agriculture's future contributions to growth.